A place to talk - Crisis at the cathedral

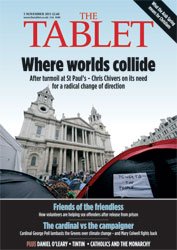

St Paul’s Cathedral has faced turmoil with the resignation of three staff, including its canon chancellor and dean, over the encampment of anti-capitalism protesters around it. The dispute has raised further questions about the role of the cathedral and its relationship with the City

St Paul’s Cathedral has faced turmoil with the resignation of three staff, including its canon chancellor and dean, over the encampment of anti-capitalism protesters around it. The dispute has raised further questions about the role of the cathedral and its relationship with the City

I love St Paul’s Cathedral. I stood on its steps moments after I’d been ordained deacon, saw a beautiful woman walk through its Great West Doors and heard a voice inside me tell me that I’d marry her! A few months later I did. So I’ve enormous sympathy with the idea that those steps and the piazza beyond them – the bridge, if you like, between church and world – are a liminal, transactional, gathering space. A place from which to show that the unhelpful post-Enlightenment distinction between sacred and secular – polarised yet further by the hardline rhetoric of the new atheists (who are the same as the old atheists but much ruder) – is bogus. Canon Giles Fraser, a thoughtful maverick of a cathedral canon – just the kind the Church of England used to appoint to cathedrals but now sadly, given the straitjacket of the appointments system and the general drift of the Church of England towards appointing middle managers to senior posts, somewhat of a one-off – was doing what instinctively he does with such passion. He opened his arms to the protesters, part of the Occupy London Stock Exchange protest, who had set up camp around St Paul’s, and affirmed not only their right to protest but the issues of corporate greed and inequality that they are seeking to raise.

These are issues that the St Paul’s Institute, of which Fraser had been director for the past two years, has done so much to animate. The institute has done so in a far more creative way than the stand-off between St Paul’s and the City in the 1970s, or the somewhat too comfortable way in which the cathedral seemed to go along with the shallow fruits of the 1980s financial boom. It was that boom which led eventually to the immorality of FTSE 100 directors threatening to almost double their pay for a second year running.

Let’s not waste too much breath on the mechanics of what happened on and from those steps. It’s easy to see with hindsight that a spirit of welcome immediately raises unavoidable health-and-safety issues. It’s all very well for former Archbishop of Canterbury Lord Carey to mock these, as he did in an article in The Daily Telegraph. But as a priest who worked on the staff of the cathedral in Cape Town – whose steps and piazza are rather more used to protest than St Paul’s, one suspects – I know only too well how the right to protest, the rights of others to safety and security, and to trade unhindered as well, not to mention the rights of various landowners, makes things tricky. Three cheers then for the dean and chapter of St Paul’s for knowing straight away that what mattered was the relationship they built with the protesters. In Cape Town we were well practised at it. We were dealing with people with whom we’d built up a relationship over years of anti-apartheid protest carried forward into the excitement of protest about issues in a newly democratised nation. St Paul’s had to achieve this in a week.

The cathedral has paid a heavy price: not only did Canon Giles Fraser resign over the proposed eviction of the protesters, but so did part-time chaplain Fraser Dyer. Then on Monday, the Dean, Graeme Knowles, who first took the decision to close the cathedral on health-and-safety grounds (then re-opened it, spoke to the protesters on Sunday but did not back down on the eviction plan) fell on his sword instead and resigned, saying his position was untenable.

After this, also on Monday, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, intervened, saying publicly that urgent issues raised by the protesters needed to be discussed. Of course mistakes have probably been made. I’ve worked as a member of a cathedral chapter myself, in Blackburn, and on the staff of another cathedral-like institution, Westminster Abbey, where the internal conversations, let alone the external ones, could be challenging to say the least. But to those who have charged the cathedral with naivety – Lord Carey, was again among them and, like a former archbishop, Lord Fisher, increasingly comes across as someone who doesn’t seem to know when less is more – I’d like to turn the tables and suggest that it’s naive in the extreme to suppose that such dynamic, organic movements and moments can be handled as if one were planning the minutiae of a state funeral.

St Paul’s Cathedral must be doing something right when Ken Costa, a senior City figure, could write a Financial Times piece, “Why the City should heed the discordant voices of St Paul’s”, which resonates with exactly the issues the cathedral has sought so faithfully to bring into focus. “There is a “pressing need to reconnect the financial with the ethical,” said Costa. “Economies,” he added, “cannot flourish without mutual trust and respect or without fundamental honesty and integrity.

“We all need”, he continued, “to learn the grammar of morality”, and to accept that “good and bad … are objective rather than subjective, real rather than endlessly pliable, relevant to public life rather than restricted to private life, and, above all, necessary.” By this point Costa had certainly climbed the steps to the cathedral door, perhaps even the pulpit steps themselves. (Indeed he has since been brought in by the Bishop of London, Richard Chartres, to head an initiative to reconnect the financial with the ethical.) He crowned it all with a sting in the tale of his sermon to smite the hind parts of many a younger banker, financier or director. “For many,” he said, “this will be like learning an entirely new language.” Which is exactly what the prominence of a cathedral like St Paul’s makes possible. At Blackburn, a good deal less prominent architecturally, but nonetheless at the heart of Lancashire, and in the hearts of Lancashire folk of all faiths and none, we used to talk about the St Mark’s Venice effect. No, Blackburn is not normally spoken of in the same sentence as Venice but, like the great cathedral of St Mark’s – and like St Paul’s with its steps and piazza – its shadow falls across a public space beyond the West Doors where people congregate to chat, to eat lunch, or simply to catch a few minutes of peace in a busy day. Could we coax them inside to discuss the issues that invariably seemed to animate these conversations? We could and we did, often encouraging between 250 and 500 people, sometimes even more, to fill the nave not simply to discuss common concerns, but also to talk to policy-makers and politicians so as to shape what subsequently happened.

A book title from a decade or more ago described cathedrals as “flagships of the spirit”. It was too self-satisfied a title to stand the test of time. But what the events at St Paul’s are showing is that – in an age where the proliferative babble of internet social networks actually masks real speaking and listening – cathedrals can still be cutting-edge places of real conversation. Perhaps they are the only central institutions left that dare to embrace the edges and the margins. People look to them as dynamic and creative places for the kind of public dialogue denied to us when politicians mostly announce policies outside of parliament, and they want them to be risk-taking places for social justice and truth. The ethics for which they stand can challenge and change the irresponsible riskiness behind a morality-free market paying dividends to the richest executives while the rest of us pay the cost. The potential that people see in them is nothing less, of course, than the radically transforming power of the Gospel.

- Truth, justice and accountability are a must to guarantee reconciliation for Sri Lanka

- Priest to cross country on foot for peace

- Explosive new book details war on unborn baby girls

- A Catholic Call to Abolish the Death Penalty in USA

- 'More guns won't help'

- Archbishop of Westminster's statement on the Royal Succession

- Anti-corporate protests to hit London

- National Justice &Peace signs up to ‘Close the Gap’

- Pope Francis Visits Refugees in Rome: Recognise The Need For Justice And Hope, And True Liberation

- Korea: Rights group also slams naval base arrests as 'serious failure of governance'

Votes : 0

Votes : 0