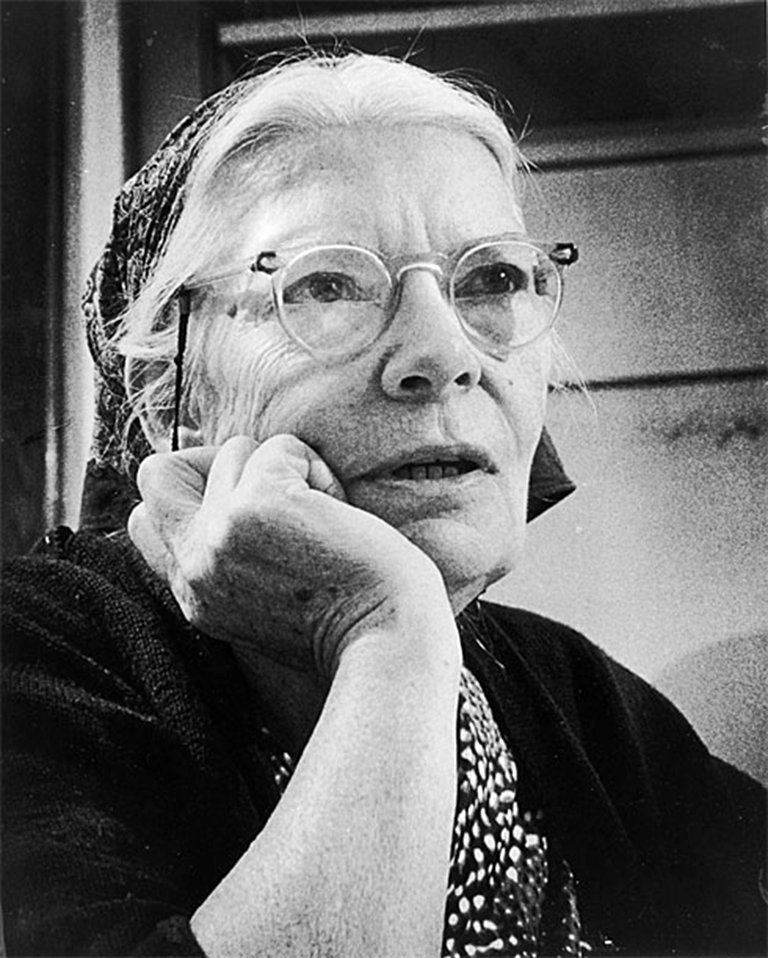

A saint for our time, now in the making

A saint for our time, now in the making. As the United States enters a period of unprecedented uncertainty, the canonisation of a radical peace activist who was imprisoned several times is becoming increasingly likely

She truly was a saint, a saint for our time, those who knew her believe – although the canonisation of this complex and intensely human woman is no fait accompli, and they retain mixed feelings about it.

She truly was a saint, a saint for our time, those who knew her believe – although the canonisation of this complex and intensely human woman is no fait accompli, and they retain mixed feelings about it.

Dorothy Day was ambivalent herself. “I don’t want to be a saint,” she famously said, “I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” She would also say: “I wish they might wait until I am dead.” Day never wanted the focus to be on her, as Pat and Kathleen Jordan, who helped to care for in her last years, confirm. She always wanted it to be on the Gospel.

What happened to me, when I phoned to ask to visit St Joseph’s, on New York’s Lower East Side, where Day lived and which is now the motherhouse of the Catholic Worker movement, has happened to many others – I am simply invited to come and help.

The men in the queue outside direct me to bang on the door of 36 East 1st Street, just off the Bowery, once New York’s “Skid Row” but now populated by trendy bars, artisan boutiques and art galleries. I am put straight to work by Nathan, who is 26 and has been living in the community for a year. Once the hour-and-a-half shift starts at 10 a.m., it goes quickly – the 28 places filled and refilled as the hungry are served with a nutritious soup, prepared fresh by Geoffrey every day.

They get fresh coffee, bread and margarine, and an endless supply of donuts and pumpkin pie, donated by local bakeries and served by volunteers, some singing cheerfully or playfully splashing the hot water in vast sinks as the plates and mugs are washed and reused. There is no time to talk, just endless requests – “more coffee please, miss” – until about 120 have been served.

St Joseph House, together with Maryhouse around the corner on East 3rd Street, which serves a daily meal to a smaller number of women, and a communal farm upstate, make up the New York City Catholic Worker community, which includes six decision-making members and a constant stream of temporary residents, volunteers and guests.

Dorothy Day was born in 1897 into a non-practising Episcopalian family; she died on 29 November 1980, aged 83. She became a journalist, activist and suffragette, living a bohemian life among socialists and anarchists, actors and artists in New York and Chicago.

From her earliest days, as she recounts in her autobiography The Long Loneliness, she was on a spiritual quest. She had several lovers, including the editor and writer Lionel Moise, the father of the child she aborted; possibly, too, the playwright Eugene O’Neill. She was also briefly married to Berkeley Tobey, founder of the Literary Guild.

She fell in love with the anarchist Forster Batterham, and had an overwhelming experience of God’s love through her love for him and in giving birth to their daughter, Tamar – whom she had baptised as a Catholic before being conditionally baptised herself. Later, she made a total commitment to the Church and its teaching, and gave up Batterham, whom she apparently loved until the end of her days, because he did not believe in marriage.

She agonised about how to lead a fully Christian life in response to the injustice and suffering she saw all around her as the Depression took hold. In 1932, on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, 8 December, when she was covering the Hunger March in Washington, she prayed in the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception for guidance, and back in New York found the eccentric French itinerant philosopher Peter Maurin on her doorstep.

He had the vision for houses of hospitality, the communal farms, and the newspaper, and a deep knowledge of Catholic Social Teaching – but he was a man of theories. Day was a practical woman, the “cipher” for Maurin’s abstract ideas; they founded the radical newspaper The Catholic Worker and worked together until his death in 1949. Day refused to pay taxes or take government funding. She protested against the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, the dropping of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Vietnam War. She went to jail many times.

Wherever Maurin or Day went and spoke about the Catholic Worker movement, around the country further communities sprang up – there are now 245 worldwide, including 216 in the United States and three in the United Kingdom. Day never wanted the movement to be large, but as her granddaughter, Martha Hennessy, says, it continues to be about “cells of good living, mustard seeds of hope amongst the current destruction”.

Catholic Worker community members still protest – for example, against the training of drone operatives in upstate New York and Nevada, against Guantanamo Bay outside the White House, and in support of the current strike of some 48,000 US prisoners against their factory pay of 1-2 cents an hour.

Cardinal John O’Connor, Archbishop of New York, had met Day and became convinced she was a saint. He called a meeting in the late 1990s of people who had known her well. There was, says George Horton, New York archdiocesan director of social and community development, an unforgettable spirit in that room. In 2000, shortly before O’Connor died, she was declared a Servant of God by the Vatican.

Under Cardinal Edward Egan, the Dorothy Day Guild was established to support the cause, which received a dramatic boost when Day was one of the four “great Americans” cited by Pope Francis in his September 2015 speech to Congress, along with Martin Luther King, Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Merton. Earlier this year, under the current cardinal, Timothy Dolan, the local canonical inquiry was formally launched.

The canonisation procedures are designed to prove a life of sanctity and heroic virtue, explains Horton. Day was a prolific writer, always explicit about her faith, producing books, articles, unattributed editorials, letters and diaries. It must all – “right down to the shopping lists” – be examined by two theological censors, appointed secretly by the archbishop. The published writings are also reviewed, by a separate “historical commission”. Fifty people who knew her are being interviewed in confidence, in a formal canonical procedure. Just now, with half the interviews completed, there is a hiatus: “We are being a bit cautious at the moment, to ensure we follow the protocol,” says Horton. But the pressure is on, as those who knew Day get older. Horton hopes the local phase might be completed within a couple of years; then the reports of the commissions and the transcripts of the interviews, along with her writings, will all be sent to Rome.

“We need her to be canonised,” says Horton. “She holds up a model to the laity to live the works of mercy. She’s an orthodox, obedient daughter of the Church. She had a devotion to the Rosary and the Eucharist. She was a ‘reader of souls’. She loved beauty … and loved abundance, and wanted it for everyone. She lived a life of total selflessness and spoke out against anti-Semitism and racism … The biggest challenge is to do right by her and to see that she is translated faithfully.”

Nonetheless, Day’s family and friends have concerns. Martha Hennessy comes and goes between Maryhouse, her family in Vermont, and her schedule of giving talks about Dorothy. Her grandmother was, she says, an incredibly integrated person who relied on the will of God. Her whole life was a pilgrimage. She was a lay person, in and of the world, and Hennessy fears that this could put her “beyond the clerical institution’s understanding” – and specifically that the Church “might focus too narrowly on her conversion and sex life and ignore the most important thing, her stance of voluntary poverty and non-violent opposition to all war”.

On 6 August 1976, aged 79, Day addressed the Philadelphia Eucharistic Congress. That day, a Mass to commemorate the military was scheduled by the bishops, who had apparently forgotten it was the anniversary of the Hiroshima bomb. She spoke about her work with the poor and her conversion, and went on to admonish the bishops, calling for an act of penance. It turned out to be her last public appearance. For sure, however her canonisation proceeds, it will be difficult to make of her a plaster saint.

Vicky Cosstick is a former assistant editor of The Tablet and a freelance writer.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0