Africa: cry, the beloved continent

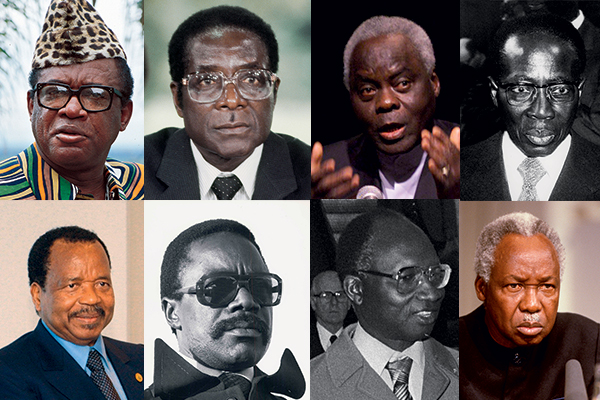

Top row (l-r) Mobutu Sese Seko; Robert Mugabe; Mathieu Kérékou and Sédar Senghor. Bottom row: Paul Biya; Albert Bongo; David Jawara and Julius Nyerere - Photos: Alamy

Conflict, poverty and corruption have stifled Africa’s potential in the post-independence era, yet the Church has been reluctant to involve itself in politics. Now one of its most prominent voices argues it is time for its leaders to urge Catholics to put their faith into action for a just society

Chris Patten’s shrewd and insightful recent article in The Tablet on the Catholic Church’s mixed record as a defender of democracy made me wonder if Africa would be suffering from its apparently interminable crisis of leadership had Catholics – who make up such a vibrant part of the continent’s social and economic life – been encouraged to become actively involved in politics. Catholics in Africa vote, of course. But there are rarely serious Catholic politicians to vote for.

I should say I’ve always liked Chris Patten, even though he became chairman of the Conservative Party in 1990, when Margaret Thatcher’s policies were having a corrosive effect on the poor and on foreign students like me. Later, I thought he might launch a bid for the leadership of the party, and become Britain’s first Catholic prime minister. In 2003, when I returned to the UK as a senior fellow at St Antony’s College, Oxford, he was contesting for the position of Chancellor. I voted for him and, when he won, two friends and I celebrated his victory with a cheap bottle of red wine over dinner.

The history of the Catholic Church in Africa records the gallant struggles and self-giving sacrifices of many brave young men and women missionaries who came from Europe to light up the so-called “dark continent” with the word of God. Inspired by the words of Jesus, “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly” (John 10:10), they provided schools and hospitals, and trained teachers and nurses and doctors and other professionals. They laid the foundation for the management and professional elite that would emerge across Africa after independence. But, despite the high moral standards the missionaries set, those they taught, who went into politics, were to make a terrible job of leading their people.

What had happened? The focus of Catholic education in Africa was on preparing young men and women to be teachers or nurses or doctors or engineers rather than political leaders. They were trained to serve rather than to lead. Catholics came to participate in politics more as voters than as candidates seeking to be voted for. This reluctance to participate more actively in politics has come at a great cost to Africa in the post-colonial era, and not just to its Catholic citizens.

The story has often been told of the chaos left by the departing colonial powers, who hurriedly tried to impose multi-party democracy in Africa. The artificial – sometimes almost arbitrary – drawing of national boundaries often created states with a fractured ethnic and religious landscape, inhospitable to the tender seeds of democracy. Europe has struggled for centuries – and sometimes still struggles – with the ideas of free elections, of the orderly and peaceful transfer of power, of ruling with due regard for the interests of every citizen, whichever political party they may support, of an independent judiciary and of a sometimes awkward and critical free press.

With little experience or training, the first generation of African leaders had great difficulties managing diversity. The notion of an “opposition” to a ruling administration was new and alien to many cultures. In many languages, the closest synonym to “opposition” was “enemy”. Post-independence politics was characterised by one-party rule and dictatorships by “strongmen”, with state brutality common and little acknowledgement of human rights, including the right to challenge the policies and competence of the ruling administration.

The Catholic Church produced a rather rich harvest of horrible dictators: Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire, Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, Mathieu Kérékou in Benin, Paul Biya in Cameroon, Albert Bongo (later to convert to Islam after visiting Libya and become Omar al-Bashir) in Gabon, David Jawara (who also converted to Islam and became Dauda) in the Gambia. Except for Sédar Senghor in Senegal and Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, there were hardly any Catholics with credible records of governance.

The cold war saw the United States frame global politics through the prism of a conflict between liberal democracy and Communism. Unsavoury figures such as Mobutu, Mugabe, Biya and Co. consolidated their hold on power by posing as “friends of West”, protecting Africa from the horrors of Communism. Church leaders, academics, trade unionists, writers, artists, and civil society groups who opposed them were banned, tortured or jailed on the grounds that they were “Communist sympathisers”. Right up to the late 1980s, Margaret Thatcher would refer to Nelson Mandela as the worst thing imaginable – a Communist.

The collapse of the Berlin wall in 1989 caught the world by surprise and generated a mixture of anxiety and excitement across Africa. There was talk of a “second liberation”. Many dictators were toppled and apartheid collapsed. But human rights and freedom were slow-burning candles. And the voice of the Catholic Church was still heard, largely through the various joint statements and documents issued by local conferences of bishops, little noticed by most Catholics, and politely acknowledged, at best, and then ignored by politicians. Beyond these appeals, despite their authority, the bishops did very little else to give a sense of direction to lay Catholics, or to stir them to be involved in politics. this has created a problem. The Church’s focus on skills and training rather than on political education, its disinclination to “take sides” in political debate outside a narrow moral agenda, has meant that, for the most part, African Catholics have not been equipped to act as a leaven working for justice in society. In the struggle against apartheid, for example – except for the extraordinarily courageous Denis Hurley, the late Archbishop of Durban, and other brave individuals – the Church blew a muted trumpet. Perhaps the presence of patrician foreign missionaries and the sluggish promotion of indigenous priests to the hierarchy delayed the injection of a sense of social responsibility.

In 1995, I had the opportunity to visit South Africa, and a meeting with Archbishop Hurley was at the top of my agenda. When I rang and introduced myself, he immediately invited me to his home for lunch. I was struck by the simplicity of a man I had admired since my seminary days. I listened to the stories of his engagement with the apartheid government. I asked him why he took such serious risks when, being a white man, he could have simply laid low. His face lit up. “I wrote my doctoral thesis on Catholic Social Teaching,” he told me. “You cannot read the Church’s social teachings and remain the same.”

Perhaps it is ignorance of Catholic Social Teaching – still neglected in many schools and seminaries in Africa – that explains the apparent coyness in speaking out about poverty, injustice and corruption. In some cases, the leadership of the Church in Africa fell victim to seduction by smiling dictators who wore their Catholic identity as medals of honour, posing as defenders of the faith but failing to see all their fellow citizens – Catholic or Protestant, Christian or Muslim – as equally God’s children.

The emergence of St John Paul II lit up the world and gave verve to Catholicism. Catholics walked with their heads high. The clarity of his voice and his message shook the foundations of dictatorships around the world. The unforgettable images of his visits to his homeland are reminders of how Communism in Europe was defeated by ideas of truth and freedom taking hold in people’s imaginations. His speeches in Africa were deep, urgent, insightful and humane. A historic Synod of Bishops for Africa in 1994 and the insightful post-synodal apostolic exhortation Ecclesia in Africa threw a searchlight on a continent desperately in need of a moral compass.

When he visited Nigeria in March 1998, we were still in the grip of the rule of Sani Abacha, and many activists were in detention or in exile. On the eve of his arrival, a newspaper ran a screaming headline that read: “The Pope Our Last Hope!” In his final address, he told Nigerians: “The children and young people of Africa must be protected from the terrible hardships visited upon the thousands of innocent victims who are forced to become refugees, who are left hungry, or who are mercilessly abducted, abused, enslaved or killed. We must all work for a world in which no child will be deprived of peace and security, of a stable family life, of the right to grow up without fear and anxiety.” Abacha died three months later. But strange and sad to say, very little has changed.

Most Africans are still trapped between a rock and a hard place. Democracy has failed to deliver its promised dividends of equal rights and opportunities, freedom and justice. Often, the military stole our freedoms and offered us little security and no development in compensation. The generals’ cure proved to be worse than the disease of corruption they promised to end. The hopes and aspirations of our people still hang languidly in suspended animation. The wealth that lies under the ground – cobalt, bauxite, diamonds, coltan, phosphate, aluminum, uranium, copper, iron ore, gold – has turned many countries into boiling cauldrons of violence. Alan Paton’s damning novel against apartheid should have been titled “Cry, The Beloved Continent”.

Africa was scarred by brutality, exploitation and slavery before the British, the French, the Portuguese and our other uninvited guests arrived. But colonialism left Africa wounded by some of the most inhuman cruelty in human history. Leopold’s ghost left in its wake a history of savagery of monumental proportions unprecedented in human history. That same cruel Belgian king was Catholic; he even sponsored missionaries. Apartheid was built on that legacy of cruel exploitation of black Africans and their wealth.

Today, we are witnessing the return of the evil contagion of military coups as a response to increasing violence and economic insecurity. In the last 12 months, there have been military coups in Mali, Guinea, Sudan and Burkina Faso. If this doleful trend is not arrested, more African states will descend irreversibly into the abyss of military dictatorship.

There is no political system without flaws, but, as Churchill famously observed, democracy is the worst form of government – except for all the others. Pope Francis has recently warned that democracy in Europe is under threat; in Africa, it is hanging on by its finger tips. We cannot simply continue to issue statements calling for peaceful elections or pronouncing on single issues such as abortion, hunger, poverty, euthanasia, or homelessness. Mere lamentation is not enough. African church leaders must seize this moment to encourage our people to embrace and defend democracy.

Chris Patten argues that for democracy to survive, it must deliver security and prosperity for citizens, and the countries which bear its colours must demonstrate their faith in the values of an open society. The four pillars of Catholic Social Teaching – the common good, the dignity of the human person, subsidiarity, and solidarity – give the Church a programme around which it can unite all people of goodwill, and address Africa’s current malaise. If it is to protect and nurture the fragile flowering of democracy in Africa, the Church must put the energy and resourcefulness of its lay men and women, and especially the energy and intelligence of its young people, to sustained and productive engagement with the state. Africa’s future depends on it.

Matthew Hassan Kukah is the bishop of the Diocese of Sokoto, Nigeria, and founder of the Kukah Centre, a policy research institute based in Abuja and Kaduna. In December 2020, Pope Francis appointed him as a member of the Dicastery on Integral Human Development.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0