Commentary to the 3rd Sunday of Lent–Year C

To Convert is to Find One’s Identity

Introduction

“Things cannot go on like this, everyone takes advantage, cheats, the abuses are systematic, insupportable and moreover no new perspective is foreseen.” We have often heard complaints like these.

“Things cannot go on like this, everyone takes advantage, cheats, the abuses are systematic, insupportable and moreover no new perspective is foreseen.” We have often heard complaints like these.

To complain is easy, to propose a solution is harder. To deplore violations of rights, to draft official communications, to proclaim one’s own indignation can also be of some benefit, but many times complaints, especially when they are reduced to formal gestures and diplomatic declarations, remain a dead letter.

Someone gets carried away by an irrepressible irritation, resentment, revenge before an injustice and comes to perform some rash gestures. The use of violence has never yielded positive results, in fact, it has always caused trouble, often irreparable.

There is another possible choice: disinterest. It’s the option of one who closes himself in his own small world. He avoids getting involved, even just emotionally, in others’ dramas, unless the political events have no repercussion on his personal or family life.

What to do? The social, political, economic reality of the world challenges us. We cannot back out on it, estranged ourselves, observe it from the outside as idle spectators. But how to intervene? There is only one correct way: today’s Word of God suggests it.

To internalize the message, we repeat:

“The Lord is merciful and gracious. He frees us from all sins and heals all diseases.”

--------------------First Reading | Second Reading | Gospel--------------------

First Reading: Exodus 3:1-8a,13-15

Israel experienced her God first as a liberator. Only later she discovered that he is also a father, mother, husband, king, shepherd, guide, ally … The reading tells how this revelation of God to his people started.

Moses is in the Sinai desert. He is there because some years before he made a serious mistake: he saw a man of his people mistreated by an Egyptian overseer. He spoke in his defense and killed the assailant (Ex 2:11-15).

Moses has an impulsive temperament. He cannot stand bullying, harassment, abuse of power against the weak. This is also demonstrated in the desert where he fled. One day he sat by a well, the girls come to water the flock and some shepherds drive them out. He does not tolerate the abuse of power, jumps up, fights the villains and helps the shepherdesses to water the livestock (Ex 2:16-22).

Prudence and experience, at some point, taught him to calm down and not to meddle in the affairs of others. He suffers being powerless when injustices are perpetrated against the weak. But what to do? If he takes action he risks being involved in very serious problems. It’s better not to think about it and let it go!

Moses takes refuge at Jethro’s, the father of the girls. He marries the daughter and begins a poor but quiet life. Each day he goes out to graze the flock of his father-in-law and wants only to be left in peace. But can someone like him forget the Israelites brothers who in Egypt are subjected to constant harassment by their bosses? God, who knows his feelings and thoughts, one day decides to reveal his plan to him: he wants to free his people from slavery.

The story of the call of Moses is built according to the classical scheme of vocations and with the usual images to present God’s manifestations.

Moses is grazing the flock of his father-in-law at Mount Horeb. Suddenly he sees a bush burning without being consumed. He approaches and hears the voice of God who, after inviting him to take off his shoes, says: “I have seen the humiliation of my people in Egypt and I hear their cry when they are cruelly treated by their taskmasters. I know their sufferings. I have come down to free them” (vv. 7-8).

Fire is one of the most common images in the Bible to indicate the presence of God. In the desert the Lord led his people “with a pillar of fire” (Ex 13:21), “he went down in fire” (Ex 19:18), “his voice in the midst of the fire” (Deut 4:33).

Here too, the fire indicates the voice of God who reveals to his servant, the difficult and risky mission he is called to do. The burning bush that is not consumed expresses very well the “flame of God” which burns inwardly and gives no respite to Moses. It is the same flame Jeremiah speaks of: “But his word in my heart becomes like a fire burning deep within my bones. I try so hard to hold it in but I cannot do it” (Jer 20:9).

The image of the bush may have been suggested to a biblical author by a curious phenomenon that takes place in the desert: by Dictamnus albus—a meter tall shrub—essential oils that catch fire on very hot days flow from it.

The sandals complete the symbolism of the scene. They are made from the skin of a dead animal. They are unclean and cannot be introduced in a holy place where only what recalls of life has access (even today they must be removed before entering a mosque).

Saying that Moses was invited to remove his sandals, the sacred author wants to say that he has come into contact with God. The inspiration he had was not his imagination or ambition, but it came from the Lord.

Now it’s possible to reconstruct what may have happened. In solitude and silence of the desert, while perhaps reflecting on the fate of his people in Egypt, Moses was enlightened. God brought him into his world; he has instilled in Moses’ heart his very own feelings, his passion for the freedom of the oppressed. He made him understand that, to realize his dream, he needed someone like him.

In this intense and profound spiritual experience, Moses became aware of the difficulties that such an arduous enterprise presented. He explained to the Lord his objection: “If I go to the Israelites and say to them: ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ they will ask me: ‘What is his name?’ What shall I answer them?” (v. 13).

In the second part of the reading (vv. 13-15) God responds revealing his name. He says to Moses: You will tell the Israelites “I am who I am” or rather I will be the one who will be (this is the most accurate translation).

Why does God want to be called in such a strange way? What does this name that recurs around 6,828 times in the Bible mean? It means: you will realize who I will be; you will see from what I will do who I am.

What will the Israelites see? Certainly not a God who sits quietly in heaven, committed to maintaining order in the accounting of sins, who does not want to be disturbed and is not interested in what happens on earth. The God who will reveal himself to Israel will be a God who lives with passion the problems of his people, who does not tolerate the oppression of the weak and intervenes to free them.

The rabbis noticed that the sacred text does not say that the Israelites cried to the Lord, but that he has seen the affliction of his people in Egypt and have heard their cry. The Israelites cried out in pain. God has heard that lament as an invocation addressed to him and decided to help them.

God does not change his name. His feelings towards those who suffer, who undergo injustice or subjected to any form of oppression and abuse remain the same. He does not even change the way he accomplishes his liberation: he uses his angels—that’s how Moses is called (Ex 23:20,23). He does his works through those who allow themselves to be educated by his word, who grow in the heart his feelings and his thoughts and who are not afraid to take risks.

Second Reading: 1 Corinthians 10:1-6,10-12

The community of Corinth is quite good, however, as it happens everywhere, there are also negative aspects: dissensions, immorality, envy. Some Christians believe that baptism is enough to be sure of salvation. Paul realizes that the Corinthians are lulled into a dangerous illusion.

To correct this false certainty he gives the example of the people of Israel. He says: all the Israelites believed in Moses and followed him. They crossed the Red Sea, were under the cloud, they ate manna and drank the water made to flow from the rock; but, because of their unfaithfulness, none of them entered the Promised Land.

The same thing can happen to Christians. They should note that the favor of God does not produce automatic and almost magical results. It’s not enough to have believed in Christ (new Moses), being baptized (the passage of the Red Sea), having received the Spirit (the protection of the cloud), having been fed of the Eucharist (the bread and wine correspond to the manna and the water in the desert). A coherent life is necessary, otherwise, they too can get lost, as what happened to the Israelites in the desert.

Gospel: Luke 13:1-9

In the first part of the passage (vv. 1-5), two true stories are reported: a crime committed by Pilate and the sudden collapse of a tower at the pool of Siloam. Pilate was not a man with a tender heart. Historians handed down several dramatic episodes that have had him as the protagonist. Today’s Gospel tells one.

Some pilgrims came from Galilee to offer sacrifices in the temple, probably on the occasion of Easter. They are involved in an act of violence.

Easter celebrates the deliverance from Egypt. It is inevitable that it awakens in every Israelite aspirations for freedom and exacerbates the feeling of revenge against Roman oppression. It is also possible that these Galileans, maybe a little fanatics, first exchanged a few and a bit heavy jokes with the guards. Then they have made some provocative gestures, and finally, from words, they passed on to action: some shoving and a fistfight.

During big feasts, Pilate usually moved to Jerusalem from Caesarea to ensure order and prevent riots. He does not tolerate even the hint of rebellion. He orders the soldiers to intervene, with no respect for the holy place. They massacre the unfortunate Galileans. A brutal and sacrilegious gesture, an insult to the Lord, a provocation to the people that consider the temple house of their God. There, even the priests, even in winter, have to walk barefooted.

Why didn’t the Lord incinerate those responsible for this crime? The Pharisees have their answer: they argue that there is no punishment without guilt. If God willed that those Galileans were slain by the sword, it means that they were laden with sins. But how to accept this explanation? The sinner is Pilate, the wicked are the Roman soldiers.

Someone goes to report to Jesus what had happened. Maybe he thinks of tearing out of his mouth a severe judgment of conviction, an anti-Roman stance. Someone thinks of involving him in an armed uprising. Faced with such a crime he can hardly urge patience and forgiveness! At least he will make a lashing statement against Pilate.

Jesus surprised his frantic and upset interlocutors. He keeps his calm and no uncontrolled word escapes from his mouth. Above all, he rules out the connection between the death of these people and the sins which they have committed. Then he invites us to learn a lesson from this incident: it should read—he says—with a call to conversion. To clarify his thoughts, he recalls another piece of news: the death of eighteen people, caused by the collapse of a tower. It probably occurred during the construction of an aqueduct at the Pool of Siloam. These people—says Jesus—were not punished because of their sins. They died of misfortune; others could have been in their place. This event, too, is to be read as a call to conversion. Jesus’ answer seems to evade the issue. Why doesn’t he take a stance in front of the massacre? His answer surprises because he has always been very real and has certainly no fear to speak his mind.

The oppressive social structures (and that of Pilate is such) are generally very solid, have deep roots and defend themselves with powerful means. It is really an illusion to think that they can be reversed at any moment. Some believe that the use of violence can be an effective, quick and safe way to restore justice. It is the worst of illusions! The use of force does not produce anything good, does not solve problems but only creates new and more serious ones.

Jesus does not comment directly on the crime committed by Pilate. He does not want to get involved in those useless conversations where one is limited to swear and to curse. He is certainly not insensitive to the sufferings and misfortunes. He is moved to tears for love of his country. However, he knows that aggression, disdain, anger, hatred, desire for revenge are useless, indeed, are counterproductive. These feelings only lead to reckless actions that complicate the situation even more.

The call of Jesus to conversion is a call to change the way of thinking.

The Jews cultivate feelings of violence, vengeance, and resentment against the oppressors. These are not the feelings of God. It is urgent that they review their position and renounce the confidence they place in the use of the sword. Unfortunately, they are not prone to conversion and so, forty years later, they will all perish (guilty and innocent) in a new massacre.

Jesus does not try to evade the problem; he proposes a different solution. He rejects the palliatives. He invites us to intervene at the root of evil. It is useless to pretend that one can change something by simply replacing those who hold power. If the newcomers do not have a new heart, not follow a different logic, everything remains as before. It would be like changing the actors of a show without changing the role that they must perform. That is why Jesus does not adhere to the explosion of collective outrage against Pilate. He calls us to conversion, proposes a change in mentality. Only people who have become different, one person with a new heart can build a new world. This is the ultimate solution.

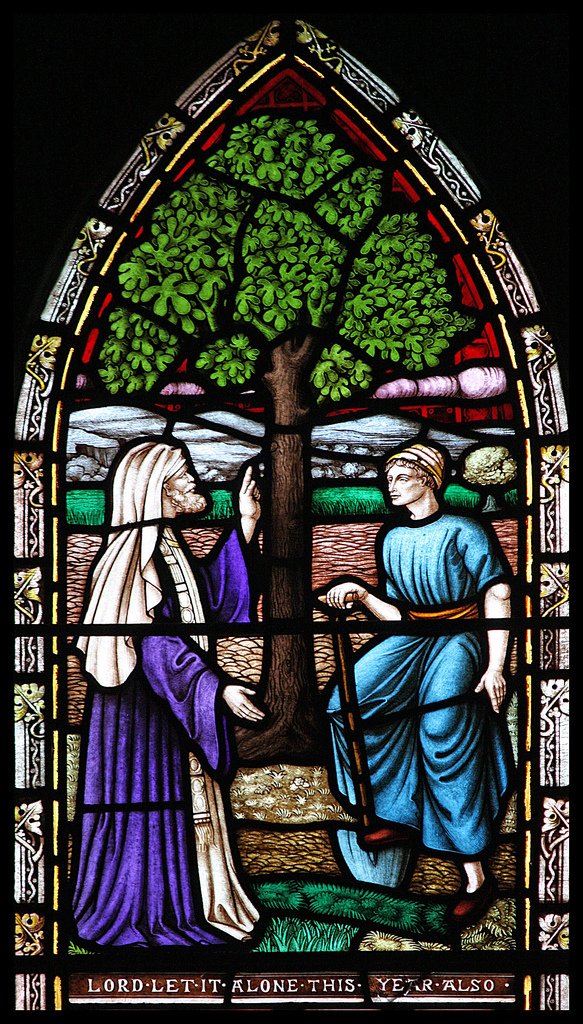

How much time is available to make this change in attitude? It may be deferred to a few months, a few years? Jesus answers to these questions in the second part of today’s Gospel (vv. 6-9) with the parable of the fig tree. The Bible speaks often of this plant that, twice a year, in spring and autumn, gives very sweet fruits. In ancient times, it was the symbol of prosperity and peace (1 Kgs 4:25; Is 36:16). In the desert of Sinai, the Israelites dreamed of a land with abundant water sources, wheat fields, and fig trees … (Deut 8:8; Num 20:5).

The message of the parable is clear: from those who have heard the message of the Gospel, God expects delicious and plentiful fruits. He does not want exterior religious practices, not content with appearances (in the spring, the fig tree bears fruit even before the leaves), but seeks works of love.

Unlike other evangelists who speak of a barren fig tree that is made almost instantly dry (Mk 11:12-24; Mt 21:18-22), Luke, the evangelist of mercy, introduces another year of waiting, before the definitive intervention. He presents a God who is patient, tolerant of human weakness, including the hardness of our mind and our heart.

This forbearing attitude, however, is not understood as indifference to evil. It is not an endorsement of the neglect, indifference, and superficiality. The time of life is too valuable because they may waste even a single moment of it. As soon as one sees the light of Christ he must accept and follow it immediately.

The parable is an invitation to consider Lent as a time of grace, as a new “precious year” which is granted to the fig tree (each person) to give fruit.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0