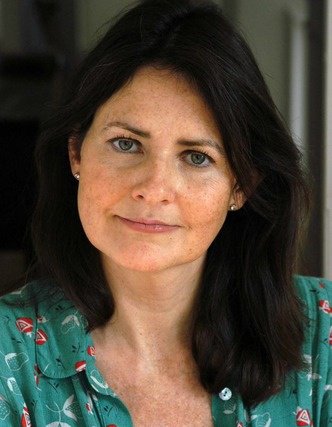

Cristina Odone is creating a network of support for parents

Odd one out: Cristina Odone is reinventing herself with an initiative creating a network of support for parents

Odd one out: Cristina Odone is reinventing herself with an initiative creating a network of support for parents

Cristina Odone made a splash in the 1990s as one of the media’s favourite It girls, the go-to Catholic commentator, but went on to broaden her range into the new century to write novels and debate politics and society as, first, deputy editor of the New Statesman, and then as a columnist in The Observer and The Daily Telegraph.

From “Thought for the Day” through Question Time to Newsnight, she was always on the airwaves, her throaty American accent instantly recognisable, and her forcefully expressed viewpoints put over with a trademark dash of folksy wisdom and references to her faith.

But of late, the woman Cardinal Hume once affectionately dubbed “the odd one” during her tenure as editor of the Catholic Herald, has largely kept out of the limelight. Why the absence, I ask, when I catch up with the 56 year old at the Legatum Institute, the Mayfair-based think tank she joined in 2013?

“I suppose I wanted to start doing something, as opposed to writing about things,” she explains. Like many a journalist before her, she had grown tired of observing the world’s problems and wanted to get her hands dirty putting them right. “Once you find that element where you feel you can bring something, it fires up a whole different part of you.”

Reproduced on paper, her words may sound slightly holier-than-thou, but that’s not how they come over in the flesh. A refusal ever to take herself too seriously, or be demure, has long been part of Odone’s charm, and that certainly hasn’t gone into purdah. Yet, even when you disagree with her, she has a warmth that makes you wish you could agree.

She is currently director of the think tank’s Centre for Character and Values, where the focus is on addressing the “values vacuum” at the heart of secular Western society left by the marginalisation of its Judeo-Christian roots. “We are not a ‘religious’ think tank,” she points out. “But ‘character and values’ allows us to look at faith, by which I don’t mean my faith, but faith in general, and how it underpins altruism.”

One way this is achieved is by inviting high-profile speakers from around the world who explore that same territory to come to Britain. In other words, Odone’s retreat from the limelight has been about redirecting that focus on to others whose ideas she finds exciting – individuals such as The New York Times columnist David Brooks. She quotes one of her favourite lines of his: “People will tell you that you have to find yourself, and I will tell you that you have to lose yourself.”

It is, she enthuses, “such a brilliant way of explaining what life is really about. It is about the other, about not putting yourself at the centre of things.” That imperative has been lost, she fears, by the edging out of faith from the public square. “It has meant that we are forcing people of faith to feel fragile, undermined, scared and therefore, possibly, to opt for extremist views, rather than be mainstream, where you can afford to be tolerant.”

She had her own much-reported brush with such rough treatment on Question Time a few years back at the hands of the historian, Tristram Hunt, then shadow Education Secretary on the Labour benches, now director of the Victoria and Albert Museum. He shouted her down for daring to suggest that nuns could be good teachers.

“That rat,” she grimaces mischievously. “What he was effectively saying was that my views were not worth listening to because I had been educated by nuns, and then he refused to apologise. But what was brilliant about the moment was that it was caught on camera, his look of absolute contempt for somebody of faith.”

Hunt was inadvertently drawing back the veil, she believes, on something that usually goes on behind closed doors. “It is the kind of contempt that a section of our establishment feels about people for whom religion is very important. Though, if that person is a Muslim or a Jew, liberal establishment figures know not to show their contempt; but with us Catholics – it is open season.”

What about Theresa May, though? This vicar’s daughter spoke candidly in the general election campaign about her Christian faith. “What she said was very interesting. She said that her faith gave her support in a moment of individual anguish, when she realised she couldn’t have children. But what she didn’t say was that her faith was colouring the way she approached policy.”

So she was trimming her sails? “No, it was brilliant to play to the audience by putting it as she did,” Odone says. “I’m not a politician, so I don’t need to appeal to voters. I don’t have to pretend my faith doesn’t colour everything, but what May was doing was saying, it colours me. And that is a step forward from where we are at the moment.”

In 2003, Odone married The Economist journalist Edward Lucas, and they have a 13-year-old daughter, Izzy. Her husband, a devout Anglican, had been married before. Though she is quick to point out that she played no part in his divorce, she no longer takes Communion, despite being a regular Massgoer. “I don’t feel I can. Even though loads of my priest friends say I can, I would feel like a fake or a fraud.”

But it’s not just her priest friends saying it. It is Pope Francis who in his exhortation on the family, Amoris Laetitia, has encouraged a more merciful approach to those divorced and remarried Catholics who seek to return to the sacraments. “That is why I am hoping Francis hurries up,” she replies. “To ensure that people who are divorced and remarried, or who marry someone who is divorced, can still take Communion.”

I’m confused. Hasn’t he made his view sufficiently clear? “I need more,” she says simply, though her pain is obvious. “I want a proper discussion and a proper decision. I think it is because I was raised in one way, and it really sticks to you.”

Marriage and motherhood have also had a profound impact on her professional life. “I was 43 when I had my one and only child,” she explains. “And I suddenly realised that I had done lots of stuff in my professional life, and quite a lot in my personal life, but I was absolutely unready to be a parent. All my friends were telling me about antenatal classes, but nobody was telling me about the 18 years after I gave birth.”

Her parenting challenge was more complex, as Lucas had two sons by his previous marriage (10 and eight at the time of his marriage to Odone), who live with them in south-west London. “Step-parenting is daunting,” she admits. “But I knew, having been a step-daughter myself, what I didn’t want to do.”

Her childhood was unusual. Her father, Augusto, an Italian World Bank executive, and her Swedish mother, Ulla, were, she recalls, “good parents but terrible as a couple”. Her father remarried and had a son, Lorenzo, who at the age of six developed adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), a genetic disease that destroys the myelin sheath that insulates the nerves, causing severe disability and death.

Odone’s father and her stepmother, with no medical training but desperate to save their beloved boy, developed a combination of oils that arrests the progress of ALD if caught early enough. Tragically for them, their breakthrough came too late to restore Lorenzo to health. In 1992, their story was given the Hollywood treatment in Lorenzo’s Oil.

“I grew up seeing parenting as something fraught,” Odone reflects, “and then with, my half-brother, as something tragic and dramatic. Parenting for me was quite an emotional and explosive relationship.”

Her fears about how she would handle motherhood led her to look at the support offered to parents in this country. “Some provision was private, some church, some local authority, some good, some bad, some chaotic, but everywhere I went, the parents felt that these classes had been life-changing or life-saving. They felt supported, they felt improved, that their relationship with their children and their spouses had improved.”

The one criticism she heard repeatedly, though, was that most courses lasted only 12 weeks, leaving parents short-changed. So working at Legatum with Juliet Neill-Hall, a mother of five with 25 years’ experience as a parenting facilitator, Odone will, from Sep-tember, be piloting a scheme in Surrey with 400 parents, where existing 12-week courses will segue into self-help groups run by a facilitator, supported by written materials that the think tank has prepared. If the trial works, the plan is to roll it out nationwide.

Its early intervention ethos certainly chimes with current priorities and thinking. “We want to help parents find their good values,” Odone stresses, “and examine how to develop and pass them on as part of a parenting class.”

It is an ambitious scheme, and if it succeeds, she will inevitably find herself back in the limelight. Has she missed any of it? “No,” she says. “Ageing makes you realise what is important and what makes you feel good. I’ve realised that what makes a difference in my quality of life is not how people perceive me, but how people relate to me. That engagement, that relationship, can never be satisfied by being on TV or radio. You have to engage on a one-to-one level. And maybe this is about finding a little bit of the missionary in me.”

Votes : 0

Votes : 0