FEAST OF THE SACRED HEART OF JESUS

THE HEART OF JESUS AND OUR HEARTS

Introduction

Devotion to the Sacred Heart has very ancient origins. It has spread in the Church especially starting from the seventeenth century through a French mystic, St. Margaret Mary Alacoque. In her autobiography, this Visitation sister tells the revelations she had. She refers to the famous twelve promises of the Sacred Heart from which the pious practice of the nine first Fridays of the month was derived. It is on the inspiration of this saint that the feast of the Sacred Heart was established.

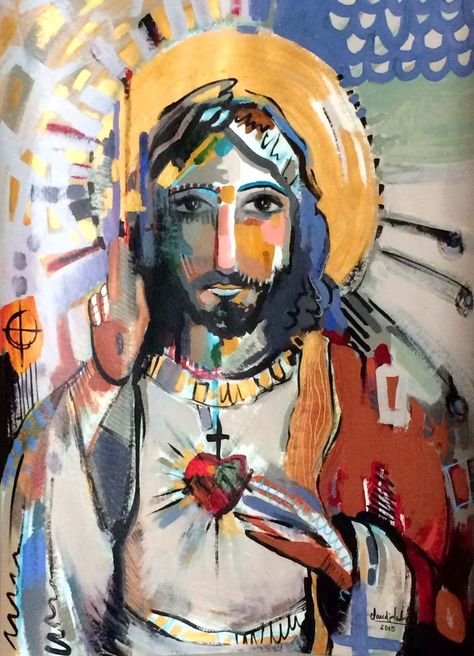

Like all forms of popular piety, this too entered into crisis after the Vatican Council II. The traditional image—the one showing the Sacred Heart ‘on a throne of flames, radiant as the sun, with the adorable wound, surrounded by thorns and topped by a cross’ conforms with the description given by St. Margaret Mary to whom He appeared. This image, too, first exposed in every home, was gradually replaced by others expressing a new theological concept and spiritual sensitivity.

Like all forms of popular piety, this too entered into crisis after the Vatican Council II. The traditional image—the one showing the Sacred Heart ‘on a throne of flames, radiant as the sun, with the adorable wound, surrounded by thorns and topped by a cross’ conforms with the description given by St. Margaret Mary to whom He appeared. This image, too, first exposed in every home, was gradually replaced by others expressing a new theological concept and spiritual sensitivity.

In the post-council period, many devotional practices have been abandoned. That of the Sacred Heart instead received a decisive boost by the conciliar spirit that led to seeking the solid foundation of every form of spirituality not in private revelations, to which—rightly—a more relative value has been given, but in God’s word.

The mystical experiences of St. Margaret Mary had, for three centuries, great importance and significant repercussions on the life of the Church. They nourished the spirituality of God’s love and fostered a virtuous and committed moral life. However, theologians put forward reservations on these revelations reported by the saint. Today, they no longer are the foundation of devotion to the Sacred Heart, which instead is solidly rooted in the Word of God.

Bible study led to some interesting discoveries. It was immediately realized that the devotion to the Sacred Heart was different from the others. It does not emphasize one of the many aspects of the Gospel message but took the center of Christian revelation: God’s heart, his passion of love for people that became visible in Christ.

In the Bible, the heart is intended as the seat of physical life and feelings, but it also designates the whole person. It is primarily considered as the seat of intelligence. We may find it strange, but the Semites think and decide with the heart, “God has given people a heart to think,”—says Sirach (17:6). He relates even some perceptions of the senses to the Israelite heart. Sirach, at the end of a long life, during which he accumulated the most diverse experiences and has gained much wisdom, says: “My heart has seen much” (Sir 1:16).

In this cultural context, the image of the heart has also been applied to God. The Bible says that God has a heart that thinks, decides, loves, and is full of bitterness. This is precisely the feeling that is invoked when, at the beginning of Genesis, the word heart appears for the first time: “The Lord saw how great was the wickedness of man on the earth and the evil was always the only thought of his heart” (Gen 6:5).

What does God feel in the face of so much moral depravity? “The Lord regretted having created man on the earth and his heart grieved” (Gen 6:6). He is unfazed—as the philosophers of antiquity thought— he is not indifferent to what happens to his children. He rejoices when he sees them happy and suffers when they move away from him because he loves them madly. Even if provoked by their faithlessness, he never reacts with aggression and violence.

The designs of the Lord, the thoughts of his heart are always and only projects of salvation. For this—the Psalmist says—“Blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord” (Ps 33:11-12).

Until the coming of Christ, people knew God’s heart only by “hearsay” (Job 42:5). In Jesus, our eyes have contemplated it. “Whoever sees me, sees him who sent me” (Jn 12:45) Jesus has assured his disciples. In his farewell address at the Last Supper, he reminded them of the same truth: “If you know me, you will know the Father also … Whoever sees me sees the Father” (Jn 14:7-9). We can come to know the Father’s heart by contemplating his heart.

When we speak of the heart of Jesus, we refer not only to his whole person but also his deepest emotions. The Gospel often refers to what he feels in the face of human needs. His heart is sensitive to the cry of the marginalized. He hears the cry of the leper who, contrary to the requirements of the law, comes up to him and, on his knees, begs him: “If you want to, you can make me clean.” Jesus—the evangelist notes—gets excited from the depths of his bowels. He listens to his heart, not to the provisions of the rabbis who prescribe marginalization. He stretches out his hand, touches him and heals him (Mk 1:40-42).

The heart of Jesus is moved when he meets pain. He shares every person's disturbance in the face of death; he feels sympathy for the widow who has lost her only child and is left alone. At Nain, when he sees the funeral procession advancing, he comes forward, comes close to the mother, and tells her: ‘Stop crying!’ And he gives her the son. No one asked him to intervene; no one had asked him to perform the miracle. It is his heart that drove him to move closer to those in pain.

The Gospel also relates a heartfelt prayer of Jesus. A father has a child with severe physical and mental problems: he stiffens, foams, and is thrown into fire or water. With the last glimmer of hope that remained, he goes to Jesus and, by appealing to the feelings of his heart, directs him a prayer, beautiful but straightforward: “If you can do anything, have pity on us and help us … “If you can!” (Mk 9:22-23). It is not an expression of doubt about his feelings, but it is a pointer to a consoling truth: he is always listening to those who suffer.

In Jesus, we have seen God crying for the death of his friend and for the people unable to recognize the one who offered salvation; we have seen God excited for the tears of a mother, touched by the sick, the marginalized, those who hunger.

The God who asks us confidence is not far away and insensitive. He is the one to whom everyone can shout: “Let yourself be moved!” The God who revealed himself in Jesus is not the impassive one the philosophers talked about. He is a God who has a heart that is moved, rejoices and grieves, weeps with those who mourn and smiles with those who are happy. An anonymous Egyptian poet wrote, towards 2,000 B.C.: ‘I seek a heart on which to rest my head, and I cannot find it, they are no longer friends.’

We are luckier: we have a heart—that of Jesus—on which to lay our head to always hear from him words of consolation, hope, and forgiveness. Today's feast wants to introduce us, through the meditation of the Word of God, in the intimacy of Jesus’ heart so that we learn to love as he loved.

To internalize the message, we repeat: “Give us, Jesus, a heart like yours.”

============================================================

First Reading: Ezekiel 34:11-16

Since its origins, Israel has been a pastoral people. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Bible speaks of lambs, sheep, and goats more than five hundred times and that the figure and the title of shepherd also applied to the king and the Lord. What characteristics of God’s heart are highlighted by this image? Today, God himself reveals it through the words of the prophet Ezekiel. His parable is set in the historical context in which it was pronounced.

In 586 B.C., the temple in Jerusalem was destroyed, and the city walls were razed. After doing all sorts of barbarism, the Babylonian soldiers deported to their homeland the good people of Israel. They left behind only the poorest in the country: some winemakers, farmers and a few craftsmen. After this catastrophe, years of total anarchy followed. Among those who remained in the land, some most cunning people took advantage of the situation of extreme need besetting the people and began to exploit those who were impoverished. They bought, sold, and trafficked unscrupulously.

Thinking back on the plight of his people, Ezekiel compares the Israelites to a flock in disarray and without a shepherd. He summons those responsible for the disastrous situation: the rulers, unworthy shepherds. His heartfelt words are of denunciation and condemnation: “But you feed on milk and are clothed in wool and you slaughter the fattest sheep. You have not taken care of the flock, you have not strengthened the weak, cared for the sick or bandaged the injured. You have not gone after the sheep that strayed or searched for the one that was lost. You ruled them harshly and were their oppressors ... My sheep wander over the mountains and high hills and were scattered throughout the land, no one bothers about them or looks for them” (Ezk 34:3-6).

What will the Lord do now? His heart, sensitive to the pain of the children, led him to intervene. Continuing to use the image of the shepherd, God opens his own heart, reveals his concern for the people and what he intends to do: “I myself will care for my sheep and watch over them” (v. 11). He had enjoined David: “You shall be the shepherd of my people” (2 Sam 5:2), but the response was disappointing: all the kings of Israel had acted as mercenaries. Here now is his decision: he will intervene personally; he will not make use of unreliable persons; he himself will become the shepherd. He will begin to gather his dispersed sheep and will not rest until he has recovered the last. Then, after bringing them back to the fold, he will gently heal the wounds inflicted on them. He will watch over his sheep (v. 12).

Like a shepherd who knows each sheep by name, God does not address anonymous masses where individuals do not count. He is interested in the problems of each one, calling each one by name. He will watch over each of his children so that no one will miss the call. If one arrives late, he will be worried and take care of this one more than the others. He will gather his sheep from all the places where they were scattered in a time of cloud and fog (v. 12).

The sheep go quickly astray because they have a weak sight. They see only up to five or six meters. If they are not in close contact with the flock and the shepherd, they get lost. They are disoriented by their bleating and the echoes of the mountains. Unable to find for themselves the way to the sheepfold, they wander confused till they get entangled in the brambles or plunge into ravines. They are safe only when they are united with the others.

God saves his people, gathering them into one-fold. There is no dark valley or steep hill that can stop him from reaching his sheep. His heart of a shepherd forces him to go down into the deepest depths of the abyss and certainly would even visit hell if one of his children had dropped there. He will bring them out from the nations and lead them to their own land (v. 13). The sheep that strays from their fold and wander in disarray may end up aggregated to other flocks. It has happened to Israel who, separated from her God, has fallen into other peoples' hands.

Far away from their land, Israel has never been happy. Egypt had plenty of food, but she was in the land of slavery. In Babylon, the soil was fertile, but it was the land of exile. The history of Israel is a parable: it is the experience of one who, attracted by the mirages, abandons the Lord’s house and finds himself a prisoner of robbers who enslave and threaten his life. God’s heart cannot bear to see his children in that desperate condition. He goes to take them back. He wants to rescue them from tyrants who enslaved them—vice, moral corruption, unruly passions—and to bring them back in the land of freedom.

He will pasture them on the mountains in all the valleys and inhabited land regions (vv. 13-14). We trust the words of someone only when we are certain that he loves us and wants our good. The shepherd and his flock live in symbiosis: the sheep's life depends on the shepherd, but the joy of these depends on the flock. The relationship is that of mutual trust, of communion of life. The intimacy between God and humanity is well represented by the delightful scene just mentioned in our reading—the mountains, the valleys, the plains—and developed in Psalm 23 where the shepherd and his flock are presented lying together on the lawn of an oasis, next to a source of fresh water where they are quenched after the tiring journey in the dry and dusty desert.

God does not give provisions to see if his authority is respected. He speaks to the heart. After all, he loves because he has a shepherd’s heart. He will tend his sheep and let them rest (v. 15). The true shepherd makes himself a travel companion. In Jesus of Nazareth, God became one of us. He has experienced our labors and our tiredness and did not give up in the face of any obstacle. He continued to walk up to the place of rest. Now, he continues to accompany each of us up to the ultimate goal, the house where “there shall be no more death or mourning, crying out or pain, for the world that was, has passed away" (Rev 21:4).

The reading’s final verse summarizes the kindness of God–shepherd (v. 16). He will go in search of the lost sheep and bring back the strayed one. He will bind up the wound and heal the sick, take care of the fat and the strong; He will shepherd them with justice. There is an aspect of God’s heart that has not yet been referred to and highlighted at the very end. God cares—we have seen it—for the most needy, but this is not to suggest that he will forget the one who is spiritually fat and strong. This person also—ensures the Prophet—is the object of his attentions. His love is infinite, and each one reserves a special place in his ‘heart.’

Second Reading: Romans 5:5-11

The First Reading has made us contemplate the heart of God–shepherd. He is good and only good with the sheep; he does not strike them if they turn away or get lost if they are injured. He goes in search of those who are lost, leads them back to the fold, and gently cares for them, one by one.

His heart is full of love—we are convinced—yet we continue to listen to the vicious rumor suggesting not trusting him. So many times, we let ourselves be seduced and wander away from the shepherd. The risk that God’s love is unrequited is always incumbent. How can we hope that the history of every person will end well? Who can assure us that our foolishness will not bring us so low as to be unattainable even by God?

Paul answers this distressing question: “Hope does not disappoint” (v. 5), and the reason is simple: the one who leads the game is not us, but God who knows how to handle it with unparalleled skill. He has poured out into our hearts his Spirit and knows how to involve us in his love. He does not lose heart in the face of any obstacle and does not strike when we are unfaithful.

Nothing, therefore, should damage our joy; hope will not be disappointed because it is not based on our faithfulness, on our good works, but the faithfulness of God. His love is not fragile and fickle. People—notes Paul—know how to love their friends and may rarely even come to give life to those they love. God’s love has no boundaries; he does not know enemies, but only children. While people were away from him, he gave them his most precious treasure, the Son (vv. 6-8).

If God loved us when we were enemies, how much more he will love us now that we have received his Spirit and have been made righteous. It is not possible that our sins may be stronger than his love. Even if we abandon him, he does not abandon us, “if we are unfaithful, he remains faithful for he cannot deny himself” (2 Tim 2:13).

The behavior of God for us is amazing. We know only one form of justice: to compensate those who do good and punish the evil-doer. God is ‘holy’; he is completely different from us. He grants his benefits to those who do not deserve them but distributes them free to all because no one deserves them. He does not abandon, does not refuse, does not punish. He takes care of his sheep that—as promised by Jesus—“shall never perish, no one can snatch them from his hand” (Jn 10:28).

Gospel: Luke 15:3-7

The sheep are easily lost and are devoid of a sense of direction. They are unable to return alone to the fold. Weakest and most defenseless of other grazing animals, they are in constant danger when far away from the shepherd. To speak to us of God’s heart and how valuable are each of his children to him, Jesus, who grew up in a pastoral society, has resorted to the image of the sheep that strays.

He told a parable not to clarify what needs to be done by one who has turned away from the Lord, but to introduce his listeners and us in the heart of God, to make us understand what the Father of heaven feels when a son of his gets lost. He recounted it to highlight what God is willing to do to bring home a sinner and the joy he feels when he can embrace him.

From the first centuries of the Church, this parable—one of the best known—has inspired artists who have reproduced in paintings, sculptures, and mosaics. No image of Jesus has ever been so dear to Christians as that of the Good Shepherd with a lamb on his shoulders. Some details of the story seemed unrealistic and were introduced by Jesus because they are paradoxical.

We observe the shepherd’s behavior. It is illogical: he leaves ninety-nine sheep in the wilderness to search for the lost one. We ask ourselves: does he not know that the herd is at risk in that desolate place? There are robbers, wolves and jackals, the steep paths, the ravines. To someone like him who knows all the secrets of the desert and that as a child, he learned to cope in the most challenging circumstances, there is nothing more to teach. If he behaves so, it is because love and the concern for his sheep in danger drove him mad. He is driven by the heart, not anymore by reason.

Beautiful image of the involvement of God in the human drama—sometimes through the person’s own fault, most of the time not; he is entangled in the toils of sin and is no longer able to break himself free. He aspires to a different life, wants to rehabilitate, to recover his own dignity, to be loved and accepted, in a word, to reconnect with the Shepherd who “lies down in green pastures and lead us beside still waters” (Ps 23:2). Still, he does not see how to get out of the abyss where he plunged in.

God has a caring and sensitive heart. In Jesus, we have seen him appreciate those who spiritually enjoyed excellent health, but his attentions were directed to the sick. To those who accused him of eating and drinking with tax collectors and sinners, he replied: “Healthy people do not need a doctor, but sick people do. I did not come to call the righteous, but sinners” (Mk 2:17).

The second part of the parable is all about joy and celebration. It starts with the gesture of the contented shepherd who carries on his shoulders the sheep that he has found. It is moving when referred to God. Some keepers—irritable and not caring, mercenaries who fled at the wolf's appearance—broke a leg of the sheep that used to get away from the flock. God has a heart of a shepherd, not a mercenary. He has a heart capable only of loving and doing good. He is a shepherd who “gives his life for the sheep” (Jn 10:11). He does not condemn nor punish those who did wrong. He does not condemn those attracted by the mirages which have lost sight of its Shepherd and fall into the abyss of sin. He adds no evil to that which, wandering away from him, man has already done.

In Judaism, it was taught that the Lord grants his pardon to those who are genuinely embarrassed, to those that with fasting, penance, tattered clothes, and prostrations manifest a strong desire to reform. The God of Jesus takes into his arms the lost one without checking first if there was at least a gesture of goodwill or repentance on the part of this person. The recovery is all his work.

The description of the feast is not very realistic; it is excessive. For an incident with a relatively trivial background, the shepherd runs from house to house, calling friends and neighbors, and hosts a feast whose story occupies more than half of the parable. It is the image of the infinite joy that God’s heart feels when he manages to recover his child.

The rabbis taught that the Lord is pleased with the resurrection of the righteous and rejoices in the destruction of the wicked. Jesus rejects this official catechesis and announces what the real feelings of God are. The Father rejoices not for the punishment but the resurrection of the wicked: “There will be more rejoicing in heaven over one repentant sinner, than over ninety-nine decent people, who do not need to repent” (Lk 15:7). The woman who lost her drama “after finding it, calls together her friends and neighbors, saying, “Celebrate with me, for I have found the silver coin I lost!” (Lk 15:9). The father of the prodigal son orders: “Take the fattened calf and kill it. We shall celebrate and have a feast” (Lk 15:23).

God loves and organizes the feast: “the Lord of hosts will prepare for all peoples a feast of rich food and choice wines, meat full of marrow, fine wine strained ... Death will be no more. He will wipe away the tears from all cheeks and eyes” (Is 25:6-8). “The Kingdom of heaven is like a king who celebrated the wedding of his son. He sent his servants to call the invited guests” (Mt 22:2-3). The symbol of the festival runs through the whole Bible. Human history will end with a wedding feast (Rev 19:9). Who are the guests?

The doctrine of just retribution was a staple of rabbinic theology. Jesus contradicts it openly, showing that the tenderness and solicitude of God are directed not to those who deserve it but, gratuitously, to those in need. From the earliest times of the Church, someone has deduced from these texts the invitation to commit sins, certain that help will come anyway. In the letter to the Romans, after speaking of the salvation offered freely by God to people, Paul continues: “Are we to sin because we are not under the Law, but under grace? Certainly not!” (Rom 6:15). A few years later, another prominent personality of the Church—who presents himself with the name of Judas, a servant of Jesus Christ and brother of James—warns Christians of some wicked people who have infiltrated the community and that “they make use of the grace of God as a license for immorality” (Jude 4).

It’s a foolishness that derives, like all sins, from having assimilated a false image of God, conceived as the despot who demands unjustified obedience and imposes himself with threats of punishment. Since no one can stand before him with accounts in good standing, they think of ensuring life, the guarantee of immunity, wiping the slate clean, and erasing all debts. Sin is not a spot to be erased, but a wound to heal; it is a loss, not a gain, a search for illusory happiness that does not grow but destroys, a move away from the family home where he is expected to attend the feast.

To help the sinner find himself, bring life and joy back to him soon, it is counterproductive and unfair—because it is a lie and a blasphemy—using the fear of God as leverage. It is necessary to announce to him—as Jesus does—the truth on God. He must understand that God is not a judge to fear but a friend who loves and wants to accompany him to the feast. Every moment spent away from him is a moment of love and a time of joy lost, for the sinner ... and also to God.

The parable's conclusion is surprising; nothing is said of the ninety-nine sheep left in the desert. It seems that only the lost one arrived home, carried on the shoulders of the shepherd. The prodigal son's father did not remain in the banquet hall while his older brother was out; he went out to get him. The shepherd cannot indeed celebrate until the other ninety-nine sheep are back in the fold. The loss of even one of his children would be unbearable for God’s heart. If in heaven one were lacking, God would go out to look for him. But first, he begins by putting securely those who have sinned, those who are in most need of his tenderness because they are the ones who have enjoyed less of his love.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0