Is Hell a thing of the past?

Hell is history. That’s good news for Jerry Lee Lewis, but bad news for Scotland’s Christian heritage. I doubt my ancestors shared the rocker’s panic about the eternal fire, but the presence of the devil was a cultural touchstone. The Broad and Narrow Way, which became enormously popular as a guide to biblical texts, as well as to desirable human conduct

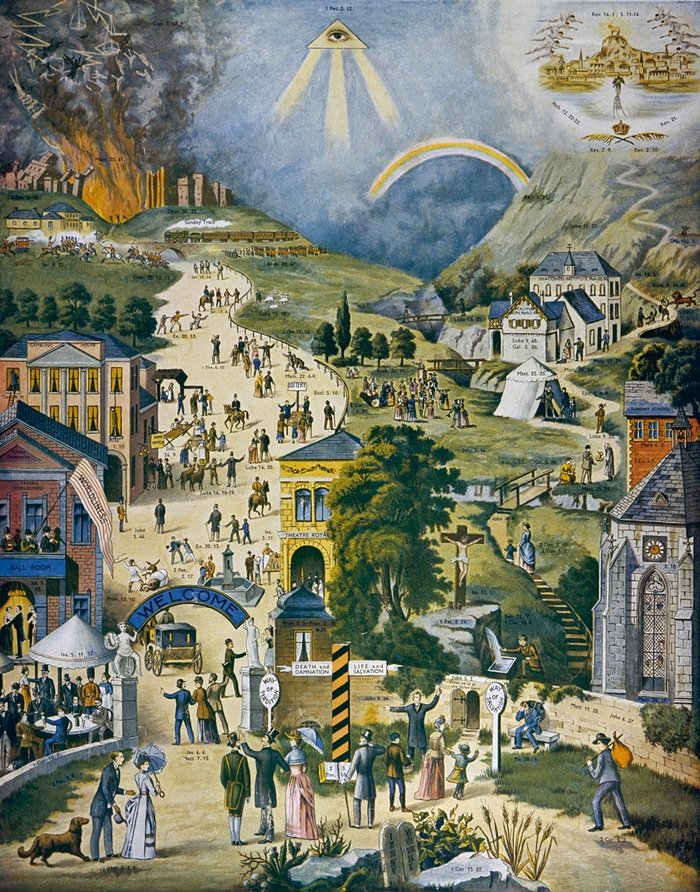

The Broad and Narrow Way – a picture designed in the mid-1800s to instruct, warn and alarm – today engages us by its alien innocence. Photograph: Mary Evans Picture Library

Saturday 3 October 2015

During the wet Scottish summer, I began to think about hell. The first trigger was Simon Hattenstone’s interview with Jerry Lee Lewis in the Guardian’s Weekend magazine. To Lewis in his old age – he turned 80 this week – the afterlife is a glorious certainty and hell a fearsome possibility. The rocker has many blots on his escutcheon, most famously his marriage to a 13-year-old cousin. “I was always worried whether I was going to heaven or hell,” he told Hattenstone. “I still am. I worry about it before I go to bed; it’s a very serious situation. I mean you worry, when you breathe your last breath, where are you going to go?” Hattenstone wondered about his earlier pill-popping, well-liquored lifestyle. His present wife, his seventh, interrupted: “That’s all forgiven. He’s going to heaven. We’re going to change the subject.” It was a very good piece.

That same Saturday afternoon in August, I hung a picture that had just come back from the framer’s. A friend gave it to me 30 years ago, and somewhere in its moves from house to house since then, it had been stored and neglected. Now, behind clean glass in a new frame, the print looked attractive and mysterious. Its title, The Broad and Narrow Way, is taken from the New Testament. According to Matthew chapter 7, verses 13 and 14: “… the gate is wide and the way is broad that leads to destruction, and there are many who enter through it … the gate is small and the way is narrow that leads to life, and there are few who find it.”

In the picture, two paths climb into a range of hills. As Matthew’s gospel suggests, the narrower is the emptier. Nothing much happens on this path. Children take their mother’s hand, men drink from bubbling springs, couples stroll towards an open-air meeting, probably of an uplifting kind. There are churches and other religious buildings on the way and at the end, in the sky above the crags, angels blow trumpets over a handsome city.

The broader path has a much larger and, it has to be said, far livelier crowd. Moustachioed dandies raise their glasses in toasts, lowlier men beat their beasts of burden, a musical trio plays above the entrance to a ballroom, boys pick pockets, families hang around pawnshops, opposing armies charge each other. There are buildings marked Theatre, Gambling House and Tavern Worldliness, all doing a roaring trade. On both paths, each of these little tableaux carries a biblical reference – “1 Peter 3:12” in the case of the eye with sunbeams streaming from it that presides over the whole scene. “For the eyes of the Lord are over the righteous … but the face of the lord is against them that do evil.” And, sure enough, as soon as the broad path ducks under a railway bridge, it enters a realm of flames, architectural collapse and human torment; perhaps the locomotive and carriages crossing the bridge and marked “Sunday trains” were God’s last straw.

The print began its life as a painting in mid-19th century Germany, and by the 1890s had become enormously popular, as a guide to biblical texts, as well as to desirable human conduct, in Protestant churches and classrooms all over the world. Elements in the picture – language, flags, the design of the locomotive hauling the Sabbath-breaking train – changed from country to country. In Britain, prints sold for a shilling each. Today reprints cost £45.99. A picture that was designed to instruct, warn and alarm had become an amusing curio only a couple of decades into the 20th century, and today represents a system of belief and instruction that engages us by its alien innocence. Drinking, dancing, gambling, borrowing, fighting, stealing: conduct that in 1890 would have set you on the road to hell soon became forgiven, occasionally even celebrated, as unchangeable aspects of the national character.

Hell was dead for most British people by the end of the first world war, which had done such a fine job with its earthly reproduction. How much Christian belief and observance died with it? How much human conduct had the fear of everlasting punishment ever really modified? These things are impossible to reckon. Personally, I doubt that my own ancestors shared Jerry Lee Lewis’s nightly panic about the eternal fire, even though as residents of Victorian Scotland they lived in a country that was strongly flavoured by a fierce and admonitory Christianity. Certainly, nothing in the memory of them suggests that they did. Then again, a historian has written of English evangelicals: “Hell and heaven seemed as certain to them as tomorrow’s sunrise, and the Last Judgement as real as the week’s balance-sheet”, and if that can be said of an English Christian movement, it can be said twice over for the Calvinists to the north.

And historian, TC Smout, attributes the decline in Scottish churchgoing to the change in emphasis from punishment to love, as well as to the developments in science that demolished literal interpretations of the Bible. The Christian tone began to falter. “Christianity from the beginning had centred on the life after death. If the church was vague about it, men reached their own conclusions: if there was a god, he was good: if he was good, he would send you to heaven … it would all come right in the end.” Smout writes that it was this “homespun logic” that caused “the death of hell, the liberation of many from psychological terrors, and the cooling of much fervour among the laity”.

There began an emptying of the pews, slowly and unevenly at first – in 1961 the Church of Scotland actually had more members than in 1931 – then at a rate that bewildered a generation that had grown up in the age when the tolling of bells was Sunday’s chief sound, and the walk to church its chief movement. In the 1920s, the Church of Scotland and its offshoots had 14 congregations on the island of the Bute. When I first began to visit Bute regularly, in the 1990s, it had six. Today it has two. There is, of course, more to this shrinkage than the devil’s absence. In an ambitious expansion scheme that promised to bring Christ to the darkest corners of the industrial revolution, the early 19th-century Kirk built 222 churches in seven years, increasing the existing stock by a fifth. Then came the schism that established the Free Church, and later the United Frees, the Wee Frees and the Wee Wee Frees, all of which needed separate churches to accommodate their differences. By 1851, according to Smout, the Presbyterian churches had enough pews to seat 63% of the Scottish population. An oversupply, as it turned out, but it was perhaps no wonder that, for a time, some could think of the Scots as the second chosen people of the Lord.

All across Scotland, churches have found new uses as dwellings, storehouses, bars and theatre venues. Many others lie abandoned – roofless, their walls sprouting bushes and small trees – in overgrown graveyards. If we saw sights like these in, say, India but with Hindu temples rather than churches, we would understand that a certain kind of civilisation had passed away. Scotland’s rapid transformation from an intensely religious society to a materialist and secular one attracts less notice. This summer as we walked among the graveyard’s long, wet grass, it was hard not to think of the devil lying there, dead among the ruins.

- Restoring religion to the public square - Faith’s role in civil society

- Anglican Bishops back Church of England breakaway congregations

- A new way of being Christian

- Anglican Bishops back Church of England breakaway congregations

- Religion and education in England and France, A sharp contrast, in theory

- Don't be embarrassed to invite the lapsed back to our broken Church

- Evangelisation is not the work of specialists but of the entire people of God

- Archbishop Gomez: Religious freedom given by God, not government

- Don't be embarrassed to invite the lapsed back to our broken Church

- Lord's Prayer cinema ad ban in England

Votes : 0

Votes : 0