Nightmare on Downing Street: An enfeebled Government face political challenges on an unprecedented scale

Political turmoil

It was, ludicrously enough, the chancellor’s stated intention of taking a ride in a driverless vehicle that said more than anything else about the parlous state of the British government in these trouble-torn times. Or, rather, the reaction of those who, laughably, are responsible for the government’s public image and who then felt it necessary to ensure that there would be no circumstances whatever, not the slightest possibility, no glimmer of an opportunity, for Philip Hammond to be allowed even to look at, let alone be photographed near, any kind of car, lorry, truck or van which did not have a driver.

It is the metaphors that are proving the undoing of this disastrous administration. In years to come, when these dreadful days are at last over and the memory of Theresa May’s government is consigned to the dustbin of history, it will be the pitiable image of a prime minister pathetically struggling to articulate her political intentions against the artificial backdrop of a slowly disintegrating stage set that will serve as her epitaph. Just as the picture of Neil Kinnock being knocked over by a wave on Brighton beach on the day of his election as Labour leader in 1983 somehow served to encapsulate his ensuing years of luckless leadership, it is the mind’s eye image that fixes the meaning of the metaphor. Watching Mrs May’s tussle at the time of her party conference speech, it was tragically evident that this was a disaster from which she would not, from which she could not, recover.

Nor will she. Like John Major in his last days at No. 10 (as derided by Norman Lamont), she in office but not in power. And yet the curious thing, which is both hard to explain and utterly puzzling to the world outside Westminster, is that Mrs May could be ousted, or obliged to resign, tomorrow; or, alternatively, she could remain in office, fatally damaged as she is, for months or even years.

I have been reporting from Westminster for 45 years and I have never seen a government in as much disarray. The law of consequences suggests that it cannot continue. But somehow it limps along. “I’ll tell you what’s going on!” Harold Wilson once declared, when confronted with an onset of particularly poisonous plotting in his own party: “I’m going on!” Mrs May does not have the authority today to make any sort of assertion like that.

A rehearsal of the circumstances is necessary here to point up the extraordinary nature of our current state of affairs. Mrs May is prime minister by default. She got the job because she was the least worst option, but she espoused a decency that was evident to all. The daughter of the vicarage, she is socially and economically conservative, but it was an Anglo-Catholic vicarage, and she has been imbued from birth with the values of citizenship and with the sense of duty and responsibility to help others in practical ways. She taught Sunday school. She has told us that her faith informs her actions, frames her thinking: “It’s part of me. It’s part of who I am and therefore how I approach things.”

But, having set out with the best of intentions, the prime minister has been beset and bested by a combination of events and bad judgement, culminating in this year’s unnecessary and calamitous general election. She remains prime minister by default, because the alternatives that could keep the Conservative party from falling apart – and from losing office – are either non-existent or too terrible for her and her advisers to contemplate. There is no candidate to succeed her who might be able to keep the party together, when the prospect of its disintegration is very real. And anything that might precipitate another general election carries the obvious possibility of a resurgent left-wing Labour Party storming into power.

That childhood inheritance of rights and responsibilities means, therefore, that she must accept the duty of leadership, however limited her ability to respond. And limited she most certainly is. She has a chancellor of the exchequer she doesn’t trust and who she would willingly replace if she could. Mr Hammond is regarded with disdain by much of the Tory party; he has an unerring ability to do or say the wrong thing and he found himself last week faced with the unusual prospect of presenting a budget he had publicly discussed in advance, knowing that it scarcely mattered, since he could not succeed whatever he did. Somewhat vacuously, he said he intended his budget “to tell the story about where Britain is going”, but in doing so drew attention to the fact that actually nobody has a clue what that story might be, thanks to the dark, heavy cloud we call Brexit obscuring every inch of the route ahead.

She has a foreign secretary in Boris Johnson who is an international laughing stock and who should have been fired. She cannot do so because (see above) she does not have the political strength and cannot afford to lose a third cabinet minister in as many weeks. She has a deputy, her first minister, Damian Green, whose usefulness is somewhat limited because of an investigation by the morality police for alleged wrongdoing that he strenuously denies. As Mrs May herself has given the morality police the upper hand in today’s febrile climate, inquiries will have to be left to take their course.

As if all this were not enough, she has a home secretary, Amber Rudd, who wants her job, an environment secretary in Michael Gove who wants anybody else’s job, a chief whip, Julian Smith, who is new in the job and has no experience, and thus runs a whips’ office with no authority to rein in a parliamentary party at war with itself. If she turns to breathe the air outside Westminster, she finds Donald Tusk, the European Council president, setting her ever more pressing deadlines. Or there is the Irish taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, rightly anxious about the impact of Brexit on the Republic’s border with Northern Ireland (wherein, of course, lies Mrs May’s House of Commons’ majority in the shape of the ten Democratic Unionist MPs).

Her political agenda is, of course, necessarily dictated entirely by Brexit, but also assisted to some extent by the pro-Brexit, anti-European parts of the press, which have lately embarked on an exercise of bullying both the prime minister and any MPs who put respect for their own consciences ahead of the votes of their constituents in last year’s referendum. This despite the fact that we have a representative democracy in this country, not a delegated one. Would it be any wonder if Mrs May did not, like the character in the new production of the play Network, have a breakdown and repeatedly scream: “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this any more”? She will need all her Christian forbearance not to do so.

It is impossible to predict what might happen next. Working all these years at Westminster, I have witnessed many crises, sat on the edge of my seat many times, wondering how each in a succession of prime ministers will weather the political trials they face – but doing so somehow always with a confident sense that right will prevail.

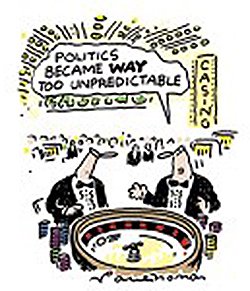

I have never known uncertainty on this scale, with such a weak and enfeebled government, unsure of its own purpose and faced with the most critical political situation for the future of the state and its institutions. “Anyone who tells you that they know what is going to happen in British politics between now and Christmas is deluding themselves,” Ken Clarke, the “Father” of the House of Commons, its longest-serving member, said this week. He spoke the truth, a rather frightening one.

Julia Langdon is a political journalist, writer and broadcaster.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0