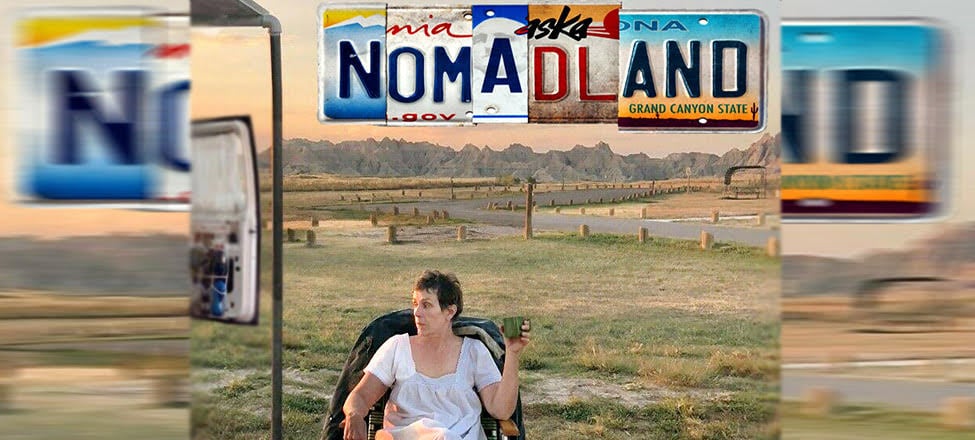

‘Nomadland’

Nomadland, winner of a Golden Lion, Golden Globes and Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Directing and Best Actress in a Leading Role, is based on journalist Jessica Bruder’s 2017 investigative book of the same name.

Director, Chloé Zhao, is a US-based, Chinese writer and producer, with two critically acclaimed movies to her credit. Both Songs My Brothers Taught Me (2015) and The Rider – A Cowboy’s Dream (2017) are marked by dramatic events that immerse and challenge their protagonists and set in the broad expanses of nature, featuring landscape shots with leaden sunsets shot through with the purple rays of the setting sun. Nomadland, made in Zhao’s recognizable style, tells the story of Fern – played with realism and resilience by Frances McDormand, of Mississippi Burning and Fargo fame. After her husband’s death, Fern leaves the city of Empire, Nevada to cross the western United States in her van, equipped as a small mobile home.

The focus of this road movie is not the mythical, adventurous or epic road of Ridley Scott’s Thelma & Louise who are seeking freedom from the patriarchy; nor is it the road of Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider, rebelliously traversing the continent in the saddle of a motorcycle; nor the road of Alexander Payne’s Nebraska, a quest for a million dollar prize.

Nomadland projects the slow rhythm of the van as it travels the asphalt of the endless, straight roads that crisscross America like deep wounds allowing encounters between “traveling travellers to be saved,” as the singer-songwriter Ivano Fossati put it.

Words and silences

Nomadland is a film that uses strong chiaroscuro images with cold tones of blue and gray as well as laconic dialogues that occasionally interrupt the largely silent course of the film. When destiny relentlessly bears down on human lives – the director tells us – words are reduced remaining unexpressed, caught in the throat. So when they emerge they take on an especially dense meaning.

Fern embarks on the journey seeking a life that fills the existential void left by the closure of the 88 year old US Gypsum factory in Empire. She had worked there with her husband who suddenly died prior to the beginning of the movie contributing to this void.

The film begins with a conversation with a guard at the factory where she worked. Fern, now ready to leave, with the last boxes to be loaded, clutches a jacket, feeling perhaps for the last time the scent of her husband and says to the guard: “Here’s what I owe you,” giving him a wad of money. And he embracing her replying: “Take care of yourself.”

These farewell words echo throughout the film, through the simple and fortuitous encounters Fern experiences during her wanderings from state to state, from job to job, along with her van. “Take care of yourself” is the dictum to which Fern responds through attention to others. In every place she stops, she will take care of others with her way of living and acting, often unconsciously, making buds blossom in the many existential deserts.

Life in the deserts

The director’s camera often lingers on the plants that manage to survive in the desert, such as cacti and succulents, or the focus lingers on the sign of the first trailer park with facilities where the woman stays. It’s called Desert Rose, as if to suggest that even in deserts it is possible for a hope, a bud, a sense to blossom.

But the deserts are not just the endless snow-covered landscapes scarred, almost like a wound, by the long, lonely road. They are also the anonymous non-places, such as an Amazon warehouse. Like the landscapes, it too is framed internally with a perspective from above, while, in the center, the conveyor belt, not unlike the road, transports brown boxes ready to be sent. The artificial neon light coldly illuminates the scene, leaving the ceiling of the warehouse in dark shadow creating a sense of gloom.

But even in this desert created by human beings, moments of personal warmth are possible In one scene Linda May, an elderly friend of Fern’s, introduces her work colleagues during their lunch break, calling each of them by their name. It is precisely in such an anonymous place, like a warehouse lost in the void, that one’s identity, one’s name, and therefore one’s story – whatever it may be – are affirmed.

Fern defines herself as someone who do not have a house when she responds to a former student she meets in a discount store, who asks her if she is “homeless” – such people are rooted in the importance of the essential. There are many scenes in which the camera lingers on cups, plates, utensils, to which the characters attribute deep symbolic value. A can opener becomes the symbol of her friendship with Dave, while Fern reciprocates with a potholder she has made. Fern’s plate set, which Dave inadvertently breaks, will be the last souvenir of her past life Tellingly it is one of the few moments in which she loses her composure. A cigarette and a lighter are the things that lead Fern and Derek, a young hobo wandering aimlessly in search of meaning, to recognize each other along the way.

Meetings

In Fern’s journey there are numerous encounters, each is characterized by simplicity and radicality and brings some knowledge, a question, or opens up a hope. At Linda’s invitation, Fern meets Bob Wells, the founder of a community of van dwellers. They gather in an area in the middle of the Arizona desert – “a training camp for aspiring nomads,” he calls it – where it is possible to stay without danger, sharing what one has and above all what one is.

Fern meets Bob Wells twice: in the opening part of the film, when she is still unable to express her sorrow at the death of her husband and, in the final part, when, after having thrown a stone into the fire that burns and warms the night in memory of her friend Swankie. It is then that she confides for the first time some moments of her life with her husband: “Bob never knew his parents and he never had children…” And if her tale begins with an absence, in this moment she also experiences a depth of love, because, as she states, “What’s remembered, lives.”

Bob, too, will respond to Fern’s confession with an account of his own life, his own pain that led him to embark on a life of helping and serving others. He says, “One thing I love most about this life is that there is no final goodbye; you know, I’ve met hundreds of people out here…I never say a final goodbye, I just say, ‘I’ll see you down the road’.”

Meeting Swankie is another pivotal moment. Swankie is preparing for a long trip to Alaska because it holds “good memories.” It will be her las because she is now elderly and she is ill. “You don’t have a spare, you’re in the middle of nowhere and you don’t have one… you can die here, you’re in the middle of the desert, far from everyone… you have to be able to ask for help,” Swankie admonishes Fern with some severity and concern – because she had asked for Fern’s help in preparing for this trip. Staring at the now setting sun, almost a symbol for the end of her life, Swankie concludes, with amazement: “Ah, I see something beautiful.”

And then there is the meeting with Dave, a fellow nomad she connects with. He decides to return home, where his children and grandchildren are. Fern visits him in his home and experiences contact with a welcoming and open family, with grandchildren, who invite her to stay with them. Dave also declares his feelings for Fern. But she understands that she is not ready for a stable existence – both in terms of emotion and space – understanding that her life will still take her further, still on the road.

Circularity of time

The film has a circular time structure. Fern will return from where she left where she again meets the guard from the first scene of the film, who lowers the shutters of the warehouse of the now disused factory, triggering a sense of déjà vu. Back inside the dusty factory walls, Fern’s eyes are teary for the first time.

If time seems to be circular, Fern’s soul has changed thanks to the encounters she has had on the road. After entering her old house, she opens a door that overlooks the steppe, endless and bounded only on the horizon by snow-capped mountains. The door is a symbol of openness, of a new phase of life, perhaps of a new understanding of the pain of one’s own existence. It is underlined also by a piano solo that is intimate, evocative, but not sad. Fern is still ready to get into her van, standing ready on the road.

DOI: La Civiltà Cattolica, En. Ed. Vol. 5, no. 7 art. 12, 0721: 10.32009/22072446.0721.12

Votes : 0

Votes : 0