Obituary – Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI

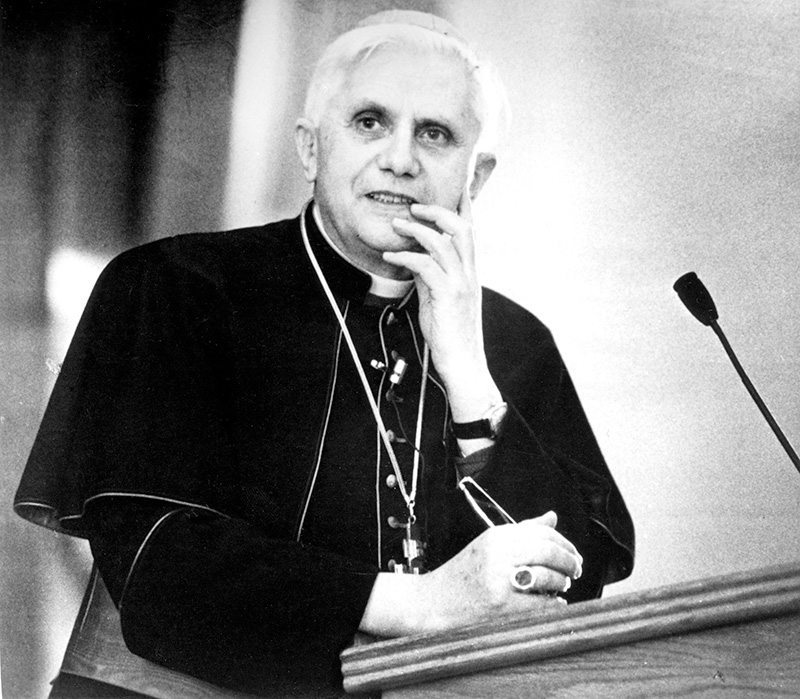

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, gives a lecture in New York in January 1988.

CNS photo/KNA

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI (16 April 1927 - 31 December 2022)

Benedict XVI, Joseph Ratzinger, who died on 31 December 2022, was one of the most influential figures in the Catholic Church during the late twentieth century and the first years of the twenty first. He developed a reputation for steely determination and rigorous pursuit of the truth, even to the extent of constraining theological exploration and pursuing those individuals he saw as trespassing beyond the pale during his years as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. As Pope, he presided over a Church that often seemed ill at ease with itself, increasingly divided over the liturgy and shamed by the failure of its bishops to deal with the scandal of child abuse. He attracted controversy and surprised both his supporters and his detractors. But nothing matched the shock of his announcement of his resignation in February 2013, the first by a pope for several hundred years.

His short papacy was considered from its beginning as a transitional pontificate, bridging the gap between the papacy of John Paul II – of the Cold War and post-Cold War – to the post 9/11 era of the twenty-first century. It concerned itself with ideas, with theology, and the life of the mind and the spirit, rather than with diplomacy or efforts to encourage greater roles for the laity and episcopal collegiality. Limitations to papal authority and the curtailment of the influence of the Curia were not on the agenda. His commitment to the documents of Vatican II came with his own personal interpretative key to the Council’s meaning and legacy. Those who had most feared his election grew increasingly convinced of his desire to dismantle the reforms of the Council, especially of the liturgy. While he became best known for his intellectual expositions of the faith, not only through his encyclicals but also through his addresses during his travels, the papacy of Benedict XVI became increasingly embroiled in controversy, in public relations gaffes, and in revelations of clerical infighting, financial corruption and chaotic mismanagement.

Joseph Ratzinger was born on Easter Saturday, 16 April 1927, in Marktl in Bavaria, the youngest of three children born to Mary and Joseph, a cook and a policeman. His early life was deeply affected by the Second World War. His father’s opposition to Nazism led to work demotions and harassment. In 1943 at the age of 16 Joseph was conscripted into anti-aircraft work in Munich, later joining the army. By the end of the war he had deserted but he was taken prisoner by the Americans, eventually being released in June 1945.

He entered seminary and was ordained alongside his elder brother Georg in 1951. Ratzinger quickly became one of the most noted young professors of theology in Germany. He taught in Bonn, Munster and Tubingen, where in 1966 his friend Hans Küng helped him secure the chair in dogmatic theology. At this time Professor Ratzinger was considered a progressive theologian, lecturing on the need for more openness and tolerance, and critical of the Vatican for leading the Church into rigidity. During the Second Vatican Council, young professor Ratzinger acted as peritus to the Archbishop of Cologne, Cardinal Joseph Frings. He helped to draft the decree on revelation, Dei Verbum, and key parts of Lumen Gentium, the dogmatic constitution on the Church. He wrote warmly of episcopal collegiality. Yet his disquiet – about the spirit of the age and about how this was influencing the Council – grew and he came to view Gaudium et Spes, the Council’s Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, as lacking in theological depth. The Council, Ratzinger came to believe, had been hijacked and its thinking distorted.

In 1977, Paul VI appointed Ratzinger to be archbishop of Munich and Freising, promoting him to the status of cardinal soon after. In 1981 Pope John Paul II called him to Rome to be Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. At the CDF, Cardinal Ratzinger made assertive orthodoxy the hallmark of John Paul’s pontificate. Theologians such as Gustavo Gutierrez and Leonardo Boff were effectively silenced while the US moral theologian Charles Curran had his licence to teach withdrawn after he had written critically on Humanae Vitae. In 1995 John Paul II’s apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis declared the debate about the ordination of women closed. It was said by some that Cardinal Ratzinger had stepped in to stop John Paul making this statement infallible.

The Wojtyla-Ratzinger partnership profoundly shaped the papacy during the eighties and nineties. As John Paul became increasingly infirm, the power and the influence of the CDF and particularly its Prefect grew, making it the most powerful congregation among the Vatican departments. In 2000 its declaration Dominus Iesus, tinged with a Catholic triumphalism some thought had been consigned to history, caused grave disquiet and hurt, not just among those concerned with ecumenism and inter-faith dialogue.

When John Paul II died in April 2005 it soon became apparent that the cardinals did not want another lengthy papacy. Cardinal Ratzinger was elected after one of the shortest conclaves in modern times. Perhaps freed by no longer having to be the Vatican’s policeman, Benedict at first seemed a gentler soul than the former prefect of the CDF. At his inaugural Mass Pope Benedict XVI spoke of “the contemporary desert, the desert of poverty, abandonment, loneliness, the emptiness of souls no longer aware of their dignity or the goal of human life. The Church as a whole and all her pastors must lead people out of the desert towards the place of life.” Rather than focus on the issues which bubbled under the surface of a troubled Catholic Church – divorce, celibacy, contraception, abortion, women’s ordination – he instead expressed wider-ranging, more fundamental beliefs. His earliest achievement was the encyclical Deus Caritas Est a beautifully written exposition of Catholic faith in the power of love.

But Benedict’s combative and controversial side came to the fore with his most notorious speech: the Regensburg address. Given during a visit home to Germany in September 2006, it was a powerful argument in favour of reason that was lost in the controversy surrounding a brief, explosive reference to Islam. Within a few days anger had spread throughout the Arab world. By the time he said that he was “deeply sorry for the reactions” towards passages in his address that “were considered offensive to the sensibility of Muslims”, mobs were burning his effigy in the streets of several cities.

In July 2007, to the delight of traditionalists and the dismay of liberals, Benedict published Summorum Pontificum, which relaxed restrictions on the use of the Tridentine Rite. “What earlier generations held as sacred, remains sacred and great for us too and it cannot be all of a sudden forbidden,” he declared. Except that, in effect, it had been, by each of his three predecessors. His lifting of restrictions on the use of the pre-Vatican Council liturgy was the clearest sign that Benedict XVI held fast to the conservatism of Joseph Ratzinger – at least in liturgical matters. A liberal at heart he was not.

Benedict rewrote the prayers in the Good Friday Liturgy celebrated according to the Roman Missal of 1962 himself, removing references to “Jewish blindness” but leaving untouched the petition that Jews be converted to Christianity. The revision did nothing to soften the offence caused to many Jews, who, after so many years of growing warmth between Judaism and Catholicism, feared that progress was being undone. In January 2009 Benedict revoked the excommunication of four men who had illicitly been ordained as bishops in 1988 by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre. One of them, Richard Williamson, was a Holocaust denier. The Chief Rabbinate of Israel broke off relations with the Vatican. It was, as The Tablet leader put it, A Damaging Fiasco.

The affair caused particular attention to be given to the visit of Benedict to Israel in the spring of 2009. Benedict acknowledged a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, voicing the need for a just solution on both Israeli soil, in Tel Aviv, and again in the Palestinian Territories. He described the wall built by the Israelis to separate themselves from the West Bank as tragic but acknowledged that hostilities had caused it to be built. Benedict was less sure-footed when he spoke at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial of the “millions of Jews killed in the horrific tragedy of the Shoah” but made no overt mention of the Nazis – which several religious and political leaders pointed out was a serious omission from a German pope.

While Benedict was instinctively conservative in matters of theology, ecclesiology and liturgy, there were ways in which he was strikingly a man of the twenty-first century. In September 2007 he told young people to take steps to save the planet “before it is too late”. It was, he said, the most urgent responsibility of their generation to protect the environment and help reverse ecological destruction.

In July 2009 came publication of his encyclical Caritas in Veritate, a critique of the way unfettered pursuit of profit had led the world to the crisis that was destroying jobs, families and communities. Like Paul VI before him, he scrutinised modern society and its lack of respect for human development. But he went further, urging humanity to treat the planet with the regard it deserved as God’s creation.

Fraternity between the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion was sorely tested by Benedict’s creation of a “personal ordinariate” that would enable Anglicans to enter into communion with Rome while retaining their Anglican patrimony. The secrecy of the negotiations – the Archbishop of Canterbury was kept in the dark – distressed many in both Churches.

As Prefect of the CDF Benedict had seen much of the paperwork from around the world indicating appalling instances of abuse by clerics and no doubt was made aware of cover-ups by bishops and church leaders. Throughout his pontificate, there were arguments over whether the CDF under Cardinal Ratzinger had done enough to deal with abuse, given that it had never offered training, or guidelines for best practice or sponsored research. He had spoken just days before John Paul’s death of the need to get rid of “the filth” in the Church. As Pope, he did what John Paul had never done: he took action against Fr Marcial Maciel Degollado, founder of the archconservative Catholic order, the Legionaries of Christ, and a notorious abuser.

Publication of two reports in 2009 exposed not only disturbing levels of clerical abuse in Ireland but the shameful incompetence of the Church in dealing with the abusers, who had not been removed from office or handed over to the police. Instead they had covered up the scandal, preferring to protect the Church’s name than deal with traumatised children. In a move unprecedented in the Church, Benedict summoned the entire hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Ireland to Rome and publicly rebuked them. Abuse of minors was, said the Pope, “a heinous crime and grave sin”. But Benedict was criticised for not making an apology and for failing to sack any bishops.

After the United States and Ireland, details emerged of similar scandals in Holland, Austria and Germany. Outside the Vatican, traumatised victims and distressed Catholics were not only dismayed by the revelations but angered by evidence of a lack of action in the past. But there was evidence that the then-Cardinal Ratzinger had attempted to act. Cardinal Schonborn of Vienna, who was close to Benedict, revealed that when he had discussed allegations of abuse against his predecessor, Cardinal Hans Herman Groër, with Ratzinger, the CDF prefect had wanted him to be investigated. But a group in the Vatican – “the diplomatic party in the State Secretariat who wanted to shove everything on the media” as Schonborn put it – had protected Groër.

The 2010 visit to the UK – which included the beatification of Cardinal John Henry Newman, long a favourite of English Catholics but also held in high personal regard by Ratzinger himself – was dominated by the central themes of Benedict’s pontificate: secularism and the role of Christianity in Europe’s history. But a somewhat softer line was developed – that there was a need for faith and secular society to come together, for there to be dialogue between them. There were predictions of large demonstrations of people protesting over abortion, gay issues and paedophilia. Anxieties melted away as the Pope landed in Scotland to begin his visit by meeting Elizabeth II at Holyrood. Benedict’s erudite address on faith and reason to the great and the good in Westminster Hall was followed by evensong at Westminster Abbey, the once Catholic church of St Peter, where Benedict knelt and prayed at the tomb of St Edward the Confessor alongside the Archbishop of Canterbury. The threatened protests came to very little. The British were surprised by the Pope, given they knew little about him other than his reputation as an arch-conservative Rottweiler; instead they discovered another Benedict: shy, charming, studious.

Nothing in fact pleased Benedict more than continuing to write theology. In November that year, as the Church’s cardinals in Rome gathered for not only the consistory but also for what was termed a summit to discuss urgent issues including religious freedom around the world and the sex abuse crisis, the Pope managed to overshadow his own gathering. An extract from his book-length interview with Peter Seewald was published on the Saturday afternoon of the gathering in L’Osservatore Romano, revealing a shift in Benedict’s thinking on the use of condoms in countering the spread of HIV/Aids. He seemed to imply that they could be used in exceptional circumstances. Those Catholics who for years had agonised over the Church’s approach to contraception saw a chink of light. So engaged were both the Church and the world by these conversations with Seewald that little was made of another comment by Pope Benedict: he could envisage that a Pope might resign, even be obliged to do so.

In the latter years of his papacy, Benedict XVI not only suffered from the inevitable decline of his health and energy but he appeared to be increasingly burdened by the demands of his office. Not only was there the distress of increasing revelations about child abuse to endure but the treachery of humankind was evident too in the leaks from his own household and the theft of his personal documents. The tensions and the troubles were engulfing the Pope. 2012 was punctuated by revelation after revelation of clerical infighting, financial corruption and mismanagement. He had been unable to stem the decline of Catholicism in Europe, or return the liturgy entirely to its pre-conciliar form, or bring the Lefebvrists back into the fold, or see the Ordinariate take off. But he had managed without attempting the showmanship of his predecessor to communicate his message. His quiet, shy persona fitted a more subdued age. Above all his homilies, his books on Jesus of Nazareth and his encyclicals are a lasting memorial to the “teaching pope”, as is his remarkable decision to retire to a life of prayer.

There were concerns that the Pope Emeritus might become an alternative Pope for those discontented with the new one. Benedict himself seemed to offer nothing but support to Francis and the two would occasionally appear together. He appeared to gain a new lease of life, giving the occasional interview and writing books and articles. After shaking the Church to its foundations with his sudden abdication, and thereby putting it on the path to reform, it was a time above all of study and prayer rather than backseat driving or troublemaking.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0