‘Our task is not to run a university’

Christopher Lamb-The Tablet - Mon, Jul 13th 2015

The loss of this prestigious higher education institution and the rejection of a planned merger with a neighbouring university was met with dismay last week. Here the Jesuit provincial explains why the order made its decision

The loss of this prestigious higher education institution and the rejection of a planned merger with a neighbouring university was met with dismay last week. Here the Jesuit provincial explains why the order made its decision

With the announcement of the closure of its flagship educational institution, Heythrop College, The Tablet last week asked if the Society of Jesus was effectively pulling out of its mission in Britain. In little over a decade, the order has withdrawn from a major parish in Wimbledon, south London, and closed both the sizeable Campion House, in west London, and a retreat centre in Merseyside, to name just three. Where does all this leave the Jesuits in this country?

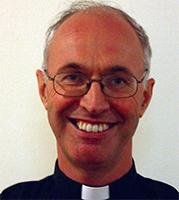

The provincial of the British Province, Fr Dermot Preston, sat down with me last Friday to explain why the society felt it could not resource a planned merger between Heythrop College, in Kensington, and another Catholic institution, St Mary’s University, just down the road in Twickenham, south-west London. He also spoke about the future of the province and how Heythrop’s mission might continue.

“Fundamentally, our task is not to run a university, it is to preach the good news,” he told me in his office in the order’s headquarters, nestling close to the five-star Connaught Hotel in Mayfair, one of London’s most expensive neighbourhoods.

Fr Preston explained that a key challenge for the order over the last decade had been trying to make Heythrop sustainable. That was why it put up around £45 million in 2009 to buy the college’s premises in a quiet square off Kensington High Street, another prime spot of London real estate. Despite this, the college still needed grants from the order to survive. This was no longer sustainable, said Fr Preston.

Beyond that, the Jesuits were concerned that a merger with St Mary’s University would require even more of their money and manpower. Fr Preston cited Jesus’ parable about building a tower without making sure you had the funds to finish it.

Measured and softly spoken, the leader of the 172 Jesuits of the British Province is a scientist by training. He reached for a medical metaphor to explain the difficulties of a partnership with St Mary’s University. “If you take a heart or another major organ and you put it into another person, what happens is you need a huge amount of resources to make sure that it is incorporated,” he said.

Fr Preston did not elaborate, however, on how much money the Jesuits were being asked to put forward. There would certainly seem to be significant funds at the order’s disposal: according to its latest accounts, the total stands at £478.2 million. Then there are its properties, which give the order an estimated total worth of around £1 billion.

In our conversation, the provincial disputed this view of the society’s assets: he described them as “bottom-line figures” and stressed that the reality is more complicated.

Firstly, he explained, the interest from the £478.2m is being used to “sustain the ministries”. These include a retreat centre in Wales, a permanent private hall in Oxford, a refugee service, parishes and schools. In fact, the interest is not sufficient for all the works currently being financed. Furthermore, certain funds are ring-fenced to provide for specific costs, such as the training of priests.

Firstly, he explained, the interest from the £478.2m is being used to “sustain the ministries”. These include a retreat centre in Wales, a permanent private hall in Oxford, a refugee service, parishes and schools. In fact, the interest is not sufficient for all the works currently being financed. Furthermore, certain funds are ring-fenced to provide for specific costs, such as the training of priests.

It should be pointed out, however, that while the interest may not be sufficient to fund all the society’s works, the capital growth of its funds is healthy: the latest accounts show that a growth in their value from £458.6m in 2013 to £478.2m last year.

But, Fr Preston stressed, “There are no secret pots of money.” Supporting Heythrop had become too difficult in its current form because of the commodification of higher education and the administrative burdens of the regulator, the Higher Education Funding Council for England.

Now, he said, the order is exploring how to set up a new institution to continue Heythrop’s work. He cited four areas on which it would focus – the teaching of theology and philosophy, the training for ministry, engagement in the public square and faith formation. This new institution would be an independent college and would incorporate the Bellarmine Institute, which is based at Heythrop, and trains Jesuit scholastics, religious and seminarians. Any new venture would be funded by the sale of Heythrop’s Kensington site, understood to be worth in the region of £100m.

Fr Preston added: “Now the task is to extract those resources to allow something new to come to birth.” He pointed out that the Religious of the Assumption, the order that sold Heythrop’s home to the Jesuits in 2009, would have a claim on proceeds of any sale to a buyer outside Catholic or educational purposes – indeed, he said, the order would get “the lion’s share”.

So, I asked, would it not have been easier for the Kensington site to be leased to a new, joint St Mary’s-Heythrop venture?

Not so, said Fr Preston. “What that would do, in effect, is transfer all the resources in the site straight into the model that would be St Mary’s,” he explained. “You need a model which is where you have Heythrop and St Mary’s working together. Unless you have a sustainable working model, then within that model the site becomes part of the business model. We looked at that and we didn’t feel that was sustainable.”

Given what Fr Preston had already said, it appeared that several of the order’s works are not sustainable. Are the Jesuits, to coin a phrase, “deinstitutionalising”, I asked.

No, said Fr Preston, because institutions are important as they provide a “platform for apostolic action”. He stressed, however, that he does not want his men “administrating more than preaching the Good News”. The order had been pulling out of missions it felt it could not sustain with either manpower or finances. “St Ignatius does not want us to get caught in particular ways of ministry,” said Fr Preston, adding that the founder of the Jesuits wanted the society to respond to changing needs.

For the Jesuits, the key to deciding where the order ought to work in the future is discerning something called “the magis” – a term that roughly translates as “more.” The concept is about not simply doing “good” but doing “the best”.

Would, in the end, a partnership between Heythrop and St Mary’s University have provided the best for the Jesuits and for Catholic higher education in Britain? Fr Preston said the order discerned that while it appeared attractive, a merger just would not have worked. So we will never know.

share :

Votes : 0

Votes : 0