Pope Francis’ Chinese puzzle: appeasing Beijing is a serious misjudgement

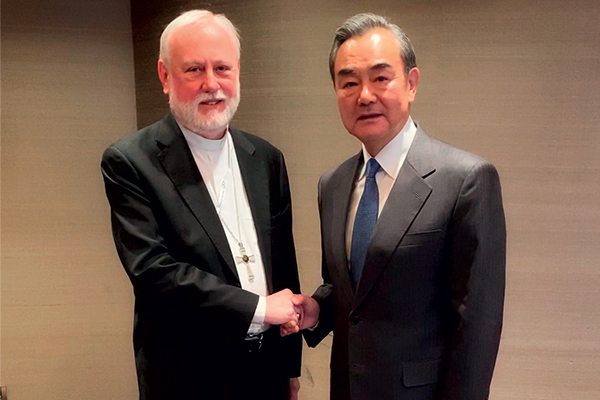

Archbishop Paul Gallagher, the Vatican’s foreign minister, greets Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi at a conference in February Photo: CNS/Vatican Media

Archbishop Paul Gallagher, the Vatican’s foreign minister, greets Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi at a conference in February Photo: CNS/Vatican Media

The former governor of Hong Kong fears that the Holy See may be making a serious misjudgement in seeming to appease the Beijing government over the status of the Catholic Church, just as China is slipping back into the most hardline dictatorship since Mao

I buy far too many books, so it comes as something of a relief to read about two that I definitely do not want to buy. In recent weeks The Tablet has referred to a couple of forthcoming books that muse about the identity of the next pope that will remain unpurchased so far as I am concerned. The fact that they both seem to make the case for a return to a constabulary Church, rather than a field hospital, a Church fit for Donald Trump, Steve Bannon and Breitbart News, is of course part of the reason for my refusal to place an order. But my reaction goes beyond this. I don’t want another pope for as long ahead as I can imagine.

Pope Francis is exactly the Pope that most Catholics, people of faith and those concerned about civic humanism on a global scale want – and, where appropriate, pray to have. A good and intelligent man, able to tell us in terms whose simplicity sometimes belies their profundity, how to live a decent, kind and generous life. He must be a wonderful confessor.

But, to borrow the last line of Some Like It Hot, “Nobody’s perfect”. Perhaps it is to Pope Francis’ credit that a world of spreadsheets and organograms would not bring out the best in him; we want a pastor not a management consultant. When he does speak of international affairs, he displays a good instinct and a pretty sure touch. In an increasingly cynical and aggressively nationalistic jungle of global diplomacy, his is an insistent voice reminding us of our common humanity and our shared responsibility for the most vulnerable. But there is one area where – scratch my head though I might – I find his thinking absolutely incomprehensible. And that is China.

The Vatican is blessed with a brilliant foreign service, linguistically talented and hugely knowledgeable about parts of the world which the rest of us know less well than we should. When I was the UK’s development minister and European external affairs commissioner, visiting an impoverished African country or somewhere in Latin America with a dreadful human rights record, I could depend on learning most about it from two sources – the bureau chief of the Financial Times or The Economist, and the local nuncio. So it’s hard to believe that the Vatican’s extraordinary convolutions over its China diplomacy could be the result of bad professional advice.

What is actually happening? The Vatican agreed a deal with the Chinese Communist Party nearly two years ago to blur the ultramontane issue of episcopal appointments. For years, there has been a distinction between the so-called Patriotic Church and the Underground Church in China. Sometimes the distinction could be fuzzy. I recall attending Good Friday services in the cathedral in Shanghai where the bishop was purportedly a member of the Patriotic Church, but had been held in solitary confinement for years. On another occasion, I went to an Underground service in a house in Suzhou which – except that the liturgy was not in Cantonese – could have been in a church in Hong Kong.

Yet there were very real differences. A friend of mine in Hong Kong, a member of a missionary order, used to spend his holidays hiking in southern China, taking money and bibles to give to communities which belonged to the Underground Church. He told me one story of knocking on a door in a remote village in search of the local bishop. A man in a dirty T-shirt answered the door nervously. When my friend asked him if he could see the bishop, he went back inside the house, and returned shortly afterwards wearing his ring.

There is a case for trying to reach some kind of rapprochement with China’s communist regime, so that all Chinese Catholics might be brought into the one Church, and be allowed to practise their faith and teach it to their children.

For many years, under the papacies of both John Paul II and Benedict XVI, there has been a small number of senior Vatican officials trying to find a way of doing this that does not require Chinese Catholics to place love of the Communist Party on a par with or ahead of love of their faith. And we know that Pope Francis has a particular esteem for Matteo Ricci, the Italian Jesuit priest who at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries founded the order’s mission to China.

It is said that the Pope would like to travel to China to beatify this great priest from Macerata. What a grand idea. But hasn’t the Vatican noticed what else is happening in China at the moment? Does it have the guile and courage to outfox a very nasty and mendacious regime in Beijing? I fear it may be cosying up to a Chinese Communist Party at the worst conceivable moment, just as it is embarking on a loutish rampage in China and beyond.

How much has the Church benefitted from this diplomatic footsie with the most hardline dictatorship in China since Mao? How many fewer Catholic pastors are today in jail than two years ago? How many Christians have been released from prison? Why are there still priests and bishops who have simply been “disappeared”? Have the officials in the Vatican noticed that the official put in charge of policy on Hong Kong cut his teeth in Zhejiang persecuting Christians and tearing down crucifixes?

The Church, I’m sure, cares about the ruthless persecution of dissidents in China. But what has it done or said about what qualifies as genocide under the UN Convention in Xinjiang, where Uighur Muslims are subjected to forced sterilisation and abortions, a policy of eugenic barbarity? How much do we Catholics care about those in Hong Kong, a significant number of whom are our co-religionists, who face prison and worse for courageously expressing their belief in democracy and the rule of law? Will anyone do anything other than mutter a doubtless sincere prayer when Martin Lee, Jimmy Lai, Cardinal Zen and Bishop Ha are silenced – or worse? How would we feel about a Chinese incursion into Taiwan, where there is a large Catholic community? Should their concerns bother us just a little?

Following the Chinese Communist Party’s assault on Hong Kong and its way of life, Cardinal Charles Maung Bo of Burma, the president of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences, appealed to Christians and people of faith throughout the world “to pray for Hong Kong”. He argued that the new law imposed on Hong Kong on 30 June “potentially undermines freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, media freedom and academic freedom”. He continued, “arguably, freedom of religion or belief is put at risk”. Given the number of Catholic schools in Hong Kong, there must presumably be disquiet at the imposition of a “Patriotic” – that is, communist – curriculum on them.

The extraordinary thing is that we almost heard something similar to Cardinal Bo’s brave denunciation of China’s actions from the Pope himself. The script of the Angelus address he had been due to give to the faithful from the balcony of the Apostolic Palace on 5 July is reported to have included an admirable and very diplomatic paragraph in which he not only expressed his heartfelt concern for the people of Hong Kong, but, after acknowledging that the issues were very delicate, went on say how easy it was to understand the strength of people’s feelings, and expressed the hope that all those involved would confront the issues in a spirit of wisdom and genuine dialogue. This, the Pope was to say, would require courage, humility, non-violence, and respect for the dignity and rights of all; he hoped that social and, particularly, religious life would manifest themselves in full freedom, as indeed several international documents mandate.

The embargoed text had been distributed to Vatican-accredited journalists. But when he came to the paragraph about Hong Kong, Pope Francis remained silent. His decision to omit the paragraph from his address has been widely reported and the omitted words themselves inevitably leaked out. Why was this paragraph in the embargoed text struck out? Naturally, theories abound.

In the twentieth century, the Vatican got into awful moral and political difficulties when trying to be too clever by half in its dealings with brutal dictators. I pray that this time they know what they are doing.

As I said at the outset, I guess nobody’s perfect.

Lord Patten of Barnes served as the last governor of Hong Kong from 1992 to 1997. He has been Chancellor of the University of Oxford since 2003.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0