The ‘Catechism of the Catholic Church’ is 30 Years Old

On October 11, 1992, on the 30th anniversary of the beginning of the Second Vatican Council, John Paul II signed the Apostolic Constitution Fidei Depositum, with which he presented the new Catechism of the Catholic Church to the clergy and “to all members of the People of God.”

A courageous undertaking

John Paul II had entrusted its preparation in 1986 to a Commission of 12 cardinals and bishops, chaired by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, following the Extraordinary Synod of Bishops of 1985 convoked by the pope for the 20th anniversary of the conclusion of the Council. In the concluding report of the Synod we read: “A great many bishops have expressed the desire that a catechism or compendium of all Catholic doctrine of both faith and morals be compiled, which will be a point of reference for the catechisms or compendia needed in the different regions. It must express sound doctrine for the daily life of Christians today.”[1] The request was endorsed by 146 bishops out of 155 present.

After the Council of Trent the Roman Catechism had gathered together in a broad and organic text a presentation of Catholic doctrine so that, in carrying out the reform of the Church desired by that Council, the pastors had a clear common reference for their teaching. Likewise, after the work of Vatican II, with the publication of its many documents and the lively discussion of their interpretation, there was felt on the part of “a great many bishops” the need for a new comprehensive text for the presentation of the Christian faith, consistent with the Council and attentive to the situation of Christians and the Church in the world today.

This was a very arduous undertaking. There had been no lack of important experiments, such as the famous Dutch Catechism and other catechisms published by various episcopal conferences, but it was observed that they “were concerned above all with examining the anthropological and sociological points of view and the method of transmission, with the result that they ended up almost losing the teachings to be transmitted along the way.”[2] It was therefore necessary to try to draft a text to express “what the faith proposes for our belief” and which would be valid for the whole Church, that is, would express what is common to the faith of Catholics, so as to serve the unity of their universal communion, beyond local differences and particular situations.

Was it possible? Many doubted it, even theologians and catechists. Not a few were convinced that it was the wrong path to take. They thought, in fact, that it was not possible to develop a catechism “of contents,” which would be opposed to the hermeneutics of the Word of God and of revelation; that a universal catechism, instead of favoring the necessary inculturation, would have hindered it and would have blocked the formulation of the catechisms of the local churches. The problem of unity and plurality emerged.[3] Of course, several of these objections continued to be expressed even after the publication of the text: “The Catechism appeared to its critics not as a possibility of unity, but as a threat against vitality and pluralism, as an attempt to bind with formulas or even to block thought courageously leaning forward, as a means of control and discipline. It has also been categorized as an attack on inculturation, which should seek new ways and forms for faith, as much in the world’s great historical cultures as in the modern technical civilization that is developing more and more.”[4]

The Commission and the Editorial Committee were not discouraged. They chose the outline already followed by the Roman Catechism, looking first of all at God and the mysteries of faith professed in the Nicene Creed and celebrated in the sacraments; then presenting how faith works in charity and is expressed in the Christian life (the Commandments in the light of the Beatitudes); finally speaking of Christian prayer, following the schema of the Lord’s prayer.

The text is therefore structured in four parts, “linked one to the other: the Christian mystery is the object of faith (first part); it is celebrated and communicated in liturgical actions (second part); it is present to enlighten and sustain the children of God in their actions (third part); it is the foundation of our prayer, the privileged expression of which is the Our Father, and it represents the focus of our supplication, our praise and our intercession (fourth part).”[5]

The original text, written in French, was sent in 1989 for wide consultation to all the bishops of the world, to Roman congregations, to theological institutes and experts, gathering about 24,000 opinions, especially on the third part. The text is therefore the result of a vast collaboration, largely of the episcopate of the whole world.[6] It is not intended to be linked to a particular “theology,” but “should faithfully and systematically present the teaching of Sacred Scripture, the living Tradition of the Church and the authentic Magisterium, as well as the spiritual heritage of the Fathers and the Church’s saints, to allow for a better knowledge of the Christian mystery and for enlivening the faith of the People of God. It should take into account the doctrinal statements which down the centuries the Holy Spirit has intimated to his Church. It should also help illumine with the light of faith the new situations and problems which had not yet emerged in the past. The catechism will thus contain the new and the old (cf. Matt 13:52), because the faith is always the same yet the source of ever new light.”[7]

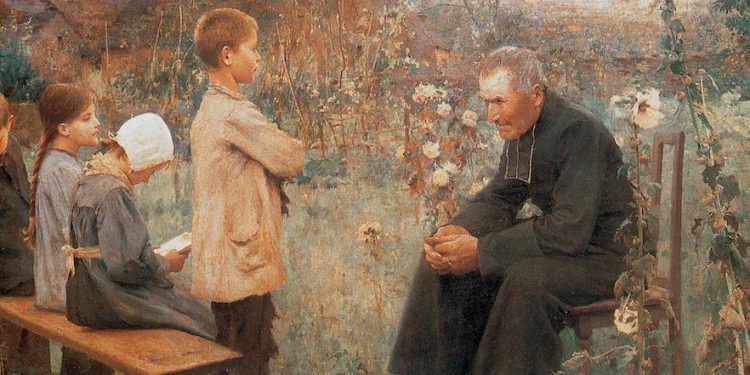

It is worth scrolling through the Index of References, from a bird’s eye view: there are countless quotations from Sacred Scripture (4,278), then from the Councils – especially Vatican II (810) – from pontifical documents, from canon law, from Western and Eastern liturgy, from ecclesiastical writers, fathers and saints of every age, up to Saint Teresa of the Child Jesus. Some illustrations, inserted at the opening of each of the four parts, are intended to recall how the Christian faith has always expressed itself also through art, the “way of beauty.” In short, through the 2,865 items of the Catechism, the great river of Christian faith and wisdom, which we can continue to draw upon in order to read today’s reality in its light and to live according to the Spirit that animated and animates it, comes down to us in all its richness, through the centuries.

It must be clear, however, that the Catechism does not itself propose “new doctrines,” nor does it attribute new value to those it presents, since its purpose is to present what is “already” the doctrine of the Church and authoritatively taught by her.

An unexpected success

In 1992 the work was completed then approved by the pope in June, but for its solemn approval he wanted to wait until the 30th anniversary of the opening of the Council, October 11. Finally, on December 7, he chose to make a symbolic presentation in the Sistine Chapel, gathering different components of the ecclesial community, including lay faithful, men and women from different language communities and continents. Meanwhile, in November, the first public presentation of the French edition took place in Paris, and in three weeks more than 500,000 copies were sold. A few months later, the Italian edition was a great success, exceeding all expectations, and the popularity continued for many other editions. The general interest in the – not only on the part of the clergy – was immediately so evident that criticism, though not disappearing, became much more muted. It is not wide of the mark to assert that the Catechism “was received with unexpected unanimity by the great majority of Catholics.”[8]

Cardinal Ratzinger – who cannot be considered the author of the work, but who certainly played a decisive role in its formulation and realization[9] – repeatedly expressed his surprise and gratitude for the outcome of the undertaking: “For me it remains a kind of miracle that in such a complex editing process a book has been produced that is in its essence internally unified and, in my opinion, also beautiful. The fact that between such different spirits, represented on the editorial board and the commission, a consensus of intentions always developed, was for me and for all the participants an extraordinary experience, in which we often even thought we could feel that higher hand guiding us.”[10] “That in a world full of contrasts, in a Church crossed by the clash of contradictory currents, such a witness of unity could have been prepared in a relatively short time is surprising: personally I had not thought it possible, and I must confess it openly.”[11]

In 1997, five years later, using observations received on the various translations (then already in 30 different languages), the Editio Typica in Latin was published, as the official reference for subsequent translations and reissues. In the General Directory for Catechesis of the same year, it was stated that the Catechism is “an official text of the Church’s Magisterium, which authoritatively gathers in a precise form, and in an organic synthesis the events and fundamental salvific truths that express the faith common to the People of God and constitute the indispensable basic reference for catechesis.”[12]

Over time, the Catechism has proved to be a very useful tool for the purpose for which it was published: to constitute a solid reference for the teaching and catechesis of the Christian people, for the presentation of the Christian faith in today’s world, for the deepening of the Christian life and its demands on believers. The Pontifical Council for the New Evangelization, for its part, has made it a pillar of its work, as can be seen from the successive versions of the Directory for Catechesis and from the structuring of the successive International Congresses on Catechesis, dedicated to the study and deepening of the different parts of the Catechism.[13] A “Compendium” of the Catechism was published in 2005. This too was mandated by John Paul II, and was also the result of work presided over by Cardinal Ratzinger. It was intended to offer a much more concise presentation of the same content, but using the classic formula of questions and answers and with greater use of images. It is a new aid, but in no way replaces the fuller text.

In the time of Pope Francis: continuity, novelty, questions

St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI continually referred to the Catechism of the Catholic Church in their teaching, having played a decisive part in its realization. Pope Francis follows the same path, well aware of the importance and usefulness of the document. This is already testified to by the lapidary words of his encyclical Lumen Fidei, the true link with Benedict’s pontificate, which define the Catechism as “a fundamental aid for that unitary act with which the Church communicates the entire content of her faith: ‘all that she herself is, and all that she believes’.”[14] Even in the spontaneous statements that often emerged in the early days of his pontificate, Pope Francis referred to the Catechism and the Church’s social doctrine to affirm, in his effective and direct language, that “it was a child of the Church.”

After all, those who have followed Pope Francis’ Wednesday catecheses have continually found – sometimes in a completely explicit form, at other times implicitly – citations or references to the Catechism. This has occurred, for example, in catechesis on the Eucharist and the sacraments, and on prayer, but also on topics of social ethics, such as the universal destination of goods. The same happens with many other texts and messages, including on sensitive topics such as therapeutic treatment and so on.

This does not mean that the Catechism should not be considered an unchangeable text, rigidly definitive and not open to improvement. This would, after all, be contradictory to its very nature of exposition of a Catholic doctrine dynamically alive in the course of human history, of a magisterium accompanied by the Spirit for the guidance of a pilgrim people of God. Evidently the questions that are asked most often (as was already the case during the preparation of the Catechism itself) concern the Third Part, on Christian life and social morals, given the changing historical situations and the dynamic relationship of the Christian faith with reality.

An example of a formulation of the Catechism that has already changed in the course of these 30 years concerns the death penalty. The first text of the Catechism, promulgated in 1992, did not exclude its legitimacy “in cases of extreme gravity” (No. 2266). Already the Editio Typica of 1997, referring to the encyclical Evangelium Vitae, published by John Paul II in 1995, had changed the formulation, declaring that “cases of absolute necessity for suppression of the offender today are very rare, if not practically non-existent” (No. 2267). Subsequently, John Paul II expressed himself again in favor of the abolition of the death penalty in his Christmas message of 1998 and in his subsequent trip to the United States. Benedict XVI had also expressed himself in a similar sense in the post-synodal exhortation Africae Munus (2011). Finally, in 2017, in the speech given on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the promulgation of the Catechism, Pope Francis explicitly called for the reformulation of the passage on the death penalty so as to better express the development of doctrine on this point in recent times.[15] The new text is blunt: “the Church teaches, in the light of the Gospel, that ‘the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person,’ and she works with determination for its abolition worldwide.”[16]

Another topic in which new formulations are not to be excluded is that which concerns responsibility toward the environment, the “common home.” Pope Francis himself, speaking to an assembly of lawyers, hinted at the possibility of developing the parts of the Catechism dedicated to ecological responsibility: “We must introduce in the Catechism of the Catholic Church the sin against ecology, the ecological sin against the common home, because it is a duty.”[17] This initiative would clearly be in line with the magisterium of recent pontiffs, and in particular, as far as Pope Francis is concerned, with the encyclical Laudato Si’ and the post-synodal exhortation on the Amazon.

Of a different nature and far more problematic are various requests for the revision of the text of the Catechism relating to themes of sexual morality, which have been frequently presented in recent times, particularly in the context of responses in this area occasioned by sexual abuse in society and in the Church.

We can recall the interventions in this regard in the Sauvé Report on the question of abuse in France.[18] But the question presents itself as much more challenging in the Synodal Way of the Church in Germany, in the course of which the critical references to the texts of the Catechism clearly manifest not so much a concern for their improvement or development, as an expectation of a broad and profound revision of the ecclesial magisterium itself on the whole subject of human sexuality, as appears from the draft texts currently being examined, for example those entitled: “Basic Lines of a Renewed Sexual Ethic,” or “Magisterial Re-evaluation of Homosexuality.”[19]

It is not for us now to enter into the merits of such complex and delicate arguments. It cannot be denied that this is one of the most challenging tests for the doctrine and pastoral care of the Church in relation to Christian life in the context of a society profoundly changed with respect to the past. Pope Francis decisively set his hand to it years ago with the convocation of the two Synods on the family and the concluding post-synodal exhortation Amoris Laetitia, but the perception of a dangerous distance between the ecclesial magisterium and the reality of Christian experience, and the looming risk of tensions and conflicts within the community of the universal Church, seems to require the continuation of a prudent and respectful path of continuity and unity that is at the same time courageous.[20] However, the problem does not primarily and directly involve discussing the texts of the Catechism, but a problem of the doctrinal and moral magisterium of the Church, which must be reflected in the Catechism.

Finally, it may be appropriate to remember that the Catechism is basically for catechesis. It is meant to be an instrument for the transmission of the faith in the contemporary world. Today this transmission, especially to the new generations, takes place in an environment radically different from the past, as a result of the “digital revolution” and its consequences. This is also a subject that we are not able to discuss here, but on which it will be necessary to reflect and on which the creativity of catechesis, further stimulated by the experience made in the time of the pandemic, will have a word to say. It will not only be a question of multiplying the translations of the same text in different languages, or the aids of various kinds to facilitate its diffusion, as is already being done commendably,[21] but of understanding its contents if the great written text, systematic and organic, is to continue to be for a long time the principal instrument of reference for the transmission of the Christian faith of the Catholic Church.

Some concluding remarks

The Catechism of the Catholic Church is an extraordinary text. It has succeeded in expressing, beyond expectations, in an organic synthesis – we can call it balanced, harmonious and pedagogically effective – Christian Catholic doctrine as it appeared at the time of the Second Vatican Council, sustained by Scripture, by the Tradition of the Church, expressed by the Councils, the popes, the great ecclesiastical authors, the saints.

It was and is a formidable reference point for the unity of the ecclesial community in a world that is extremely varied in the multiplicity of peoples, languages and cultures, and in which very rapid changes are taking place. Cardinal Avery Dulles considered it “the boldest challenge offered to the cultural relativism that today threatens to erode the content of the Catholic faith.”[22]

In the course of the past 30 years it has constituted, and continues to constitute today, a solid and reliable reference for teaching and Christian formation – and we would say also for the spirituality – of popes, bishops, priests, catechists, lay men and women. Even its critics recognize its nature as an authoritative reference text.

But the Catechism is not to be considered rigid, fixed, definitive or immutable. As an expression of the history of the Christian faith, it must remain as such, and therefore dynamic and alive. Just as from the beginning it was not meant to be an obstacle, but a means of support for inculturation, so also today it must remain a point of reference, a base, a precious instrument for the Church’s journey – assisted and guided by the Holy Spirit – in history.

Therefore it can develop. Pope Francis has given us a concrete example of this with regard to the death penalty. But in such a rapidly changing world other points can and should be usefully reformulated or added. We have given some examples of areas of crucial importance. But it must always be a reflection of the common faith of the Church, preserving unity under the guidance of the Magisterium. And the whole Church will have to continue to seek unceasingly for the best ways and effective language for the proclamation of the faith and its transmission, continuing to trust in the accompaniment of the Spirit.

DOI: La Civiltà Cattolica, En. Ed. Vol. 6, no.10 art. 9, 1022: 10.32009/22072446.1022.9

[1]. Enchiridion Vaticanum, vol. 9, Bologna, EDB, 1758, No. 1797.

[2]. E. Guerriero, Servitore di Dio e dell’umanità. La biografia di Benedetto XVI, Milan, Mondadori, 2016, 262.

[3]. The journal Concilium devoted an entire issue (No. 4 of 1989), edited by J. B. Metz and E. Schillebeeckx, to the discussion of these themes.

[4]. J. Ratzinger, “Relazione al Congresso Catechistico Internazionale”, in Oss. Rom., October 15, 1997, 6.

[5]. John Paul II, Apostolic constitution Fidei Depositum, October 11, 1992, No. 3.

[6]. Among the responses, 16 were from Roman congregations, 28 from episcopal conferences, 23 from groups representing 295 bishops, 797 from individual bishops.

[7]. John Paul II, Apostolic constitution Fidei Depositum, op. cit., No. 3.

[8] . E. Guerriero, Servitore di Dio e dell’umanità…, op. cit., 268.

[9] . We cannot forget the important part played by the editorial secretary, Christoph von Schönborn, OP, later Archbishop of Vienna and Cardinal. We signal his interesting article on the orientations followed in the conception and reception of the Catechism: “Il Catechismo della Chiesa Cattolica nelle Chiese particolari”, in R. Fisichella (ed), Il Catechismo della Chiesa Cattolica. Testo integrale e nuovo commento teologico-pastorale, Vatican City – Cinisello Balsamo (Mi), Libr. Ed. Vaticana – San Paolo, 2017, 813-824.

[10]. J. Ratzinger, “Il Catechismo della Chiesa Cattolica e l’ottimismo dei credenti”, in Communio, No. 128, 1993, 17.

[11]. Id., “Relazione al Congresso Catechistico Internazionale”, op. cit., 6.

[12]. General Directory for Catechesis, No. 124, taken up in No. 184 of the new Directory for Catechesis from the Pontifical Council for the New Evangelization, Vatican City, Libr. Ed. Vaticana, 2020, 130.

[13]. The III International Congress of Catechesis, held in Rome, September 8-10, 2022, was dedicated to the Third Part of the Catechism.

[14]. Francis, Encyclical Lumen Fidei, June 29, 2013, No. 46.

[15]. Cf. Francis, Address to Participants at the Meeting Promoted by the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization, October 11, 2017.

[16]. “Rescript on the New Drafting of No. 2267 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church on the Death Penalty”, dated August 1, 2018, and “Letter to the Bishops About the New Drafting of No. 2267 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church on the Death Penalty”, from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, dated August 2, 2018.

[17]. Francis, Address to participants at the 20th World Congress of the International Criminal Law Association, November 15, 2019.

[18]. Several paragraphs of the Sauvé Report (www.ciase.fr/medias/Ciase-Rapport-5-octobre-2021-Les-violences-sexuelles-dans-l-Eglise-catholique-France-1950-2020.pdf/), in particular Nos. 932-946 and recommendation No. 10, are dedicated to an examination and criticism of the formulation of various points of the section on the Sixth Commandment of the Catechism. In our opinion, on an unprejudiced reading of the text of the Catechism, many of the specific criticisms of the Report are highly questionable. In any case, they appear to be guided by a concern to insist more on the primacy of respect for the person and attention to victims, and more in general reflect a line of moral theology that deems it inadequate to want to contain the treatment of the problems of human sexuality within the framework of the Sixth Commandment. We note that the French bishops have not taken a position on these issues, but have launched a broader process of consultation and reflection. Cf. F. Lombardi, “Continuing the Fight against Abuse: The Sauvé Report and the French Bishops”, in Civ. Catt. En, March 2022, https://www.laciviltacattolica.com/continuing-the-fight-against-abuse-the-sauve-report-and-the-french-bishops/

[19]. www.synodalerweg.de/dokumente-reden-und-beitraege/. At the recent session of September 8-10, 2022, the indicated texts were approved by a majority of participants in the second reading.

[20]. Some reflections from Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, the 10th anniversary of whose death on August 31 we recalled were already going in this direction. See, for example, C. M. Martini – G. Sporschill, Conversazioni notturne a Gerusalemme. Sul rischio della fede, Milan, Mondadori, 2008.

[21]. We can think of the “Compendium” of the Catechism itself, published in 2005, or of the Youcat series, produced in various languages specifically for young people, or of the recent “Videocatechism of the Catholic Church”, distributed by San Paolo in 15 DVDs, as well as various series of Catholic TV broadcasts,. In this regard, the theme of the “reception” of the Catechism should be examined in depth; cf. C. Farey, “Recezione del Catechismo della Chiesa Cattolica”, in R. Fisichella (ed), Catechismo della Chiesa Cattolica. Testo integrale e nuovo commento teologico-pastorale, op. cit., 825-834.

[22]. A. Dulles, “The Challenge of the Catechism”, in First Things, No. 1, 1995.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0