‘The Chosen’ – When Jesus becomes a TV series

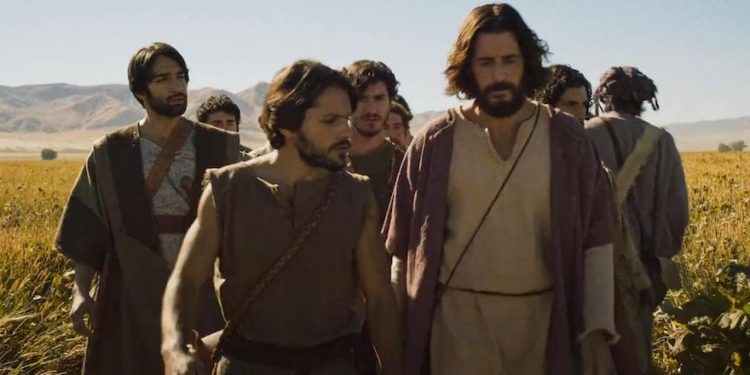

The series was conceived within an explicitly Christian framework with an approach that is intended to be ecumenical. Writer and director Dallas Jenkins[1] is an Evangelical, but the actor who plays Jesus, Jonathan Roumie, is a Catholic.[2] The private French channel C8 decided to broadcast the first season from December 20 and 27, 2021, and for the occasion the lead actor traveled to France. The launch in France was promoted by both Catholic[3] and Protestant circles and considered an opportunity for evangelization.

Only two seasons out of the seven planned have been broadcast, so before getting to the strengths and weaknesses of the program, an important observation must be made. An overall assessment on the television and theological levels cannot be given until the series has been completed (or not!). Filming both the Passion and the Resurrection (or rather, the effect only of the latter , because the actual moment of the Resurrection itself is not recounted in the Gospels) involves very significant and specific difficulties, as was the case with Mel Gibson’s 2004 film, The Passion of the Christ.

Undeniable qualities

It is worth noting first of all the strengths and real qualities of the series. To put it briefly, the series is written, acted and produced to a high standard. This is sufficient to make the whole credible. As in any film or television production, you can certainly find this or that character to be more or less convincing, but overall the castings are consistent, in particular, the characters of Mary Magdalene, Nicodemus and Matthew, while obviously the plot revolves around Jesus. He is eminently human, can play with children (s.1 ep.3), laugh, make jokes or work with his hands like a good carpenter, which is his trade. As Chris DeVille writes, “The Chosen’s Jonathan Roumie plays Jesus as someone you’d actually like to hang out with, projecting divine gravity accented with easygoing warmth. He cracks jokes; he dances at parties.”[4] Jesus’ character is simultaneously empathetic and sympathetic and this contributes to the credibility of the whole person. Jesus manages to combine genuine austerity and natural authority with a disarming smile. He is very human, gentle and yet firm at the same time. We see this in his natural interaction with everyone, and that is great. This one reason alone would justify the series.

The choice of such a medium as a TV series, has the merit of allowing an accurate presentation of the characters, of giving them a depth that no film could provide. In fact, in the first season Jesus is somewhat in the background, and this is an excellent ploy. He is talked about; he appears fleetingly, and some people set off to walk with him.

In terms of characters, it was a wise choice to start with the presentation of Mary Magdalene and especially, in a more original way, Nicodemus (who is one of the most engaging and coherent characters in the series), given the importance they will have at the end of the Gospel narrative. The apostles are introduced almost one at a time with their own characters and history. We see them grappling with their doubts, their misunderstandings, their jealousies. Viewers will note their enthusiasm and emotion at certain moments, the solidarity that gradually builds among them, even when they continue to be overwhelmed by events and are unable to fully understand their master. All of this corresponds quite well to what we know from the Gospels.

The script writers[5] clearly assume the fictional aspect of the background of the characters and some of the dialogue and situations.[6] They opened the first season with a shrewd disclaimer: “Viewers are encouraged to read the Gospels.” The series thus allows viewers to identify much more with the characters of the community gathered around Jesus than in earlier films, where all the action is constantly focused on Jesus. This new approach creates a positive effect: the apostles and women who followed Jesus were people like us, with their issues, inconsistencies, and even their failures, but this did not prevent them from walking with him, even if they did not fully understand him. The time and effort spent on character development has proved worthwhile.

Although the realization is not always at the same level, some scenes stand out for their evocative power. Such is the case with the exorcism of Mary Magdalene and the way in which, in a long nine-minute wordless sequence, the life of the paralytic at the pool of Bethsaida (cf. John 5:1-18) from his accident to his encounter with Jesus is presented. We then understand a little better what it means to be in this situation for 38 years, and how this left him terribly isolated and diminished his humanity and his hope.

The positive aspects of the first season are still present in the second. When the apostles discuss among themselves without Jesus (s.2 ep.3, and the discussion of Messianism), are excellent episodes. The encounter with the Samaritan woman is done well. There is an interesting process that is used twice that, in our opinion, is original and legitimate. At one point, the script has Jesus talking with a shepherd in a crowd to recreate the context of the parable of the lost sheep, giving a kind of realistic retelling of the possible source of a parable. More boldly, the parable of the Good Samaritan becomes an actual event, basing the parable on a real event.

There is an understated – yet very positive – insistence on highlighting the role of women. Reflecting this, the beginning of Luke chapter 8 is fully respected. In short, some scenes are very well done, and sometimes very moving. The episode of Magdalene’s “fall” is spiritually very powerful (s.2 ep.6). Jesus is a compelling presence, both as a man of prayer and a good speaker, determined and caring for others. Overall, the script is concerned with placing Jesus in the context of the Judaism of his time.[7] The central idea of writing fiction that combines the essential episodes of the Gospel with an added narrative fabric is legitimate in its approach as it reveals the humanity of both Jesus and the other characters. As Chris DeVille puts it, “Take it from a Christian and a critic: The Chosen is as well made and entertaining as many network dramas.”[8]

Understandable but questionable choices

The series is shot in English (taking care to use somewhat “exotic” speech patterns, with the exception of the Romans, with their bizarre accents). Gibson was braver in his choice of Aramaic. But we must recognize that this challenge was too great to be met. Why give the characters Hebrew names (on the whole, with some oddities) and not use Yeshua for Jesus? It is unlikely the viewers will not recognize the key character! Also, one character rightly reminds us that there are countless “Jesuses” (i.e. Yeshuas), but we do not meet any of them. Similarly – though we recognize that this is not determinative – the written Jewish characters are those of today, which in no way match those of an earlier age. Since the average viewer will not read and they are rare in the script, why not make a little effort to be more authentic? So too, we meet many Africans in Capernaum and Jerusalem, while they were rare in Judea and Galilee (certainly not present in the Jewish population of Galilee). Can one imagine a film about France in the Middle Ages, or Ming China, with so many Africans? One can then speculate that this is a “color-blind” strategy, as Netflix did for Bridgerton, for example. This would be a defensible decision. But, in this case, why only have secondary characters, servants, and no apostles? This makes the casting choice stranger.

Another choice seems surprising to us from a historical point of view. According to the opinion of the vast majority of historians, there were no Roman legionaries stationed in Galilee at that time. The region was under the direct jurisdiction of Herod. It also seems to us that, in addition to historians, rabbis could have been consulted. Some of the details of the cult are very contemporary (of Talmudic times, at least), while on other points the rites are not really followed, even on very simple things: for example, on the fact that a prayer usually ends with “amen.” The Pharisee Shammai, in the second season, seems to be a caricature that has no real justification. On the same subject, the Gospels clearly point out that Jesus attended Sabbath prayers in the synagogue and on occasion preached in the synagogue. This element is strangely absent from the series. There are a few expressions in the script that a theologian of today could have helped rewrite. For example, when it says that Jesus “was building a kingdom” (s1 e5). This verb is never used by Jesus nor is it found in the Gospels: the kingdom of God is welcomed or observed, but not “built.”

These observations, however, do not go to the heart of the plot. The scenario raises other issues that require discussion.

Some background issues

Let us start again with the apostles, who are obviously a strong feature of these first two seasons. There is a rather romantic view of the first four apostles, the fishermen. They are presented as small artisanal fishermen, whereas they were undoubtedly (at least the sons of Zebedee) local fishermen in their own right. Recall that Capernaum was one of the towns in an almost industrial belt devoted to fishing, in which Magdala stood out. But the key point is that the relationship with John the Baptist is almost obliterated, both for the apostles and for Jesus.

All the Gospels agree that Jesus’ public ministry began with his baptism by John the Baptist. Here, however, Jesus seems to begin his ministry earlier (very curiously, in the year 26, a date not entirely far-fetched, but defended by very few historians), and no baptism is presented. Jesus speaks little of John the Baptist, and Peter and Andrew do not really seem to have been pious Jews inspired by the Baptist. However, one cannot understand Jesus without understanding his relationship to John the Baptist. The surprising approach here depends, in our opinion, on the screenwriters’ Christology.

Why make Simon (not yet Peter) an ungodly collaborator with the Romans? And what about Matthew? To think of him as an adolescent with Asperger’s syndrome and a lonely tax collector is as far-fetched as it gets. Imagine the scene in France just before the Revolution: can we think of an Ancien Régime tax collector being like Matthew? On the other hand, we recognize that the actor is excellent, the character is very appealing, and this is a real plus for the series.

All the Gospels are placed on the same level, as if they had the same value in terms of historicity. The Gospels with infancy narratives, which have a very different hermeneutical status from those of Jesus’ public life, are treated at the same level of historicity, and this to the point of ridiculousness; Jesus meets an Egyptian woman and starts speaking fluent Egyptian! Aside from the fact that the sojourn in Egypt, as far as we know, is not considered historical by any scholars, how could Jesus speak thirty years later a language heard for so little time as a child and never subsequently used? At one point, Jesus is arrested and questioned by the Romans, and he is asked (frankly, it is not clear why) if he has been to the Far East, and he replies, “No, but people from there came to visit me when I was a child.” This answer may have been intended to raise a smile, or perhaps not.

We also note the presence of a tablet that Matthew carries everywhere. One gets the impression that, after some time, Jesus asks him to write down what he says, which may foster the idea that the Gospels are a literal reconstruction of what Jesus said and did, but this is misleading. The Gospels are a later ecclesial theological elaboration, based on oral stories and traditions transmitted by the disciples.[9] The chosen approach risks favoring a theology with fundamentalist tendencies. As a result, Jesus can be depicted as saying to the Samaritan woman exactly what he says in John’s Gospel, and Johannine Christology is mixed without nuance with that of the Synoptics (which greatly weakens the narrative and theological approach of Mark, for example). Similarly, we see Jesus and John meeting before the latter’s death (to criticize Herod’s marriage) and recalling the beautiful hymns of their parents ( the Magnificat and Benedictus). This, too, makes us smile, but does not seem to be the director’s intent.

There is something even more surprising. We know that all the Gospels agree that Jesus chose 12 apostles at the beginning of his public mission, so why mention the number and then show Jesus with fewer than 12 disciples? By the end of the second season, while we have already seen a good number of signs performed by Jesus and the traveling mission has already begun, the group is not yet complete. One can understand the desire to have narrative space to flesh out each of the 12 apostles, but could this not have been done before the departure on an itinerant mission? The Gospels mention the women who followed Jesus from Galilee: Mary Magdalene is not alone, but part of a group (Susanna, and Joanna among them). Certainly, the manner in which her following took place has caused much ink to flow among scripture scholars, but why present Mary Magdalene alone for so long?

Thus, in our view there is a link between the significant marginalization of the character of John the Baptist and a defective Christology. We recognize that Jesus is moved inwardly by the testimony of the Baptist. By privileging a Jesus who speaks like he does in John’s Gospel, and thus provokes an immediate messianic confession from the disciples (at the lakeside, for example, joining Luke 5, for the scene and the expression “fishers of men” of Mark and Matthew), the scriptwriters do not give the disciples the time to make an inner journey – evoked by the Synoptics – of reflection on the mystery of the person of Jesus (“Who then is this, that even the wind and the sea obey him?” Mark 4:41; Matt 8:27; Luke 8:25). Jesus has an absolute awareness of his own identity (as in the Fourth Gospel), and he says so from the beginning to the disciples; it is thus that he intervenes in a conversation in which, mentioning the Son of Man, he adds: “It’s me, by the way.” This is embarrassing because in the Gospels Jesus never says it this way, in the first person. Of course, this makes one smile , but it is at odds with the Christology of ambiguity, which is a constant of the Jesus of the Gospels. Jesus responds, “It is you who say so” (at least in the Synoptics, but here we run into the very great difficulty of keeping John and the Synoptics together, if we take John as reporting at the same level as the other three Gospels). This problem will become more and more difficult for the writers to solve as the series progresses. How will the creators be able to give the confession of Peter at Caesarea Philippi its full importance when everything is already known and said? By placing the four Gospels on exactly the same plane and, in particular, John’s Christological statements on the same plane as the patient journey of the Synoptics, the scriptwriters compress the experience of the first community, that is, the time of the journey to the writing of the four Gospels, the time of the Church. It is inevitable that their desire to situate the four Gospels on the same plane leads them into dangerous dilemmas later on.

Conclusion

It seems to us that the series can be profitably viewed by families, young people, and as part of catechetical formation. Its quality gives a pleasing consistency to both Jesus and the disciples. There are some real gems, such as when Jesus proclaims his Beatitudes while looking down from the hill at the disciples’ camp. One can appreciate some spiritually relevant dialogues, enriched by the benevolent and credible presence of Jesus, but one must be critical of the scriptwriters’ work with regard to the Gospel texts, which oscillates between excessive fidelity (Gospels of infancy, Johannine texts) and historically dubious inventions. It will be necessary to recognize that questionable options have been made (the beginning in the year 26; the strong marginalization of John the Baptist’s role in the story of Jesus and the other apostles; Jesus’ self-designation as “Son of Man” in favor of a dominant early use of “Messiah”; and the beginning of Jesus’ itinerant public mission without the Twelve ) and that some script choices are tied to a certain problematic American evangelical Protestant theology.[10]

If we evaluate the series with discernment, it can help us to gain insight into the Gospels, and that is a good thing. The fact that its directors end their second season with an error – a sign that they do not take themselves too seriously – is very happy. We look forward to the next episodes!

DOI: La Civiltà Cattolica, En. Ed. Vol. 6, no.5 art. 8, 0522: 10.32009/22072446.0522.8

[1] Born in 1975, he is the son of Jerry B. Jenkins, an evangelical writer who achieved great success with the Left Behind book series.

[2] There were two very positive reviews in America: M. G. Mangano, “The Chosen is the Jesus TV show your very Catholic aunt keeps telling you to watch. And you should” (July 2, 2021); and N. Schneider, “The Chosen dares to imagine stories about Jesus and the disciples that aren’t in the Gospels. It’s a revelation” (August 13, 2021).

[3] The SAJE production company, close to the Emmanuel Community.

[4] See “Christian America’s Must-See TV Show”, in The Atlantic (www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2021/06/the-chosen-jesus-tv-show/619306), June 27, 2021.

[5] The lead screenwriter, Dallas Jenkins, is actually part of a team that includes Tyler Thompson and Ryan Swanson.

[6] As Nathan Schneider writes, “The major creative achievement of American evangelicalism in recent years – with a Catholic in the starring role – is essentially midrashic.”

[7] Despite some clarifications to which we will return later.

[8] Cf. “Christian America’s Must-See TV Show”, op. cit.

[9] With the exception of the source of the logia (Q), but this should not be considered as transmitted as a notebook, but is already a theological elaboration.

[10] We think that some Protestants would agree with these reservations.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0