The Diana legacy

The Diana legacy

Britain’s very public grief: How the loss of Princess Diana changed our response to death

In the summer of 1997 I was – like many people at the time – more than a little intrigued by Princess Diana. I was working on the newsdesks of The Independent and The Independent on Sunday; my day began with scanning the papers, and they were brimming with stories about Diana. Like many women, I sympathised with her over her problems with her ex-husband, her difficulties with the former in-laws, and her desire to be the best possible mother to her two young sons.

In the summer of 1997 I was – like many people at the time – more than a little intrigued by Princess Diana. I was working on the newsdesks of The Independent and The Independent on Sunday; my day began with scanning the papers, and they were brimming with stories about Diana. Like many women, I sympathised with her over her problems with her ex-husband, her difficulties with the former in-laws, and her desire to be the best possible mother to her two young sons.

What most struck me, though, was her genius for empathy. She never wore gloves and always warmly touched those she met, unlike other gloved, formal royals; she would crouch when she met small children or elderly people who couldn’t stand up; and she never patronisingly bent over someone in a wheelchair but would kneel beside them.

But in the summer of 1997, Diana’s life seemed not so much about empathy but hedonism. It was very different to her humanitarian work earlier that year when she had visited Angola with the Red Cross to campaign against landmines. She had spoken out about them, calling for a ban; and she had also met victims, embracing them, just as she had with Aids victims years before.

Diana returned again to the landmines campaign with a trip to Bosnia at the beginning of August. But for the rest of that summer she seemed more of a playgirl princess, dashing from holiday to holiday, pursued by the paparazzi. A divorced woman – her marriage to the Prince of Wales had formally ended the previous year – she was photographed on the yacht of Mohamed Al-Fayed, the controversial owner of Harrods, sometimes with princes William and Harry in tow, sometimes alone with Fayed’s son, Dodi. The tabloids paid vast sums for pictures of the pair.

At The Independent, we disdained such stories; we were focused on politics, especially New Labour’s election triumph in May. And the paper famously only reported royal stories, such as the birth of Prince William, with a paragraph. That was about to change.

On Saturday 30 August, Diana and Dodi Fayed’s dash about Europe took them to Paris. Late that night, their car set off from the Ritz Hotel, and slammed into a concrete pillar in the Pont de l’Alma underpass. By 4 a.m. on Sunday, Diana was declared dead from her injuries caused by the crash.

News of the accident filtered out bit by bit – first that she was injured but OK, then that she had suffered a brain injury, and finally that she was dead. On the Sunday morning, the late editions of the morning’s papers had the news; TV channels ran wall-to-wall coverage. Tony Blair, the new Prime Minister, whose instinct for reading the public mood at that time was as strong as Diana’s had been for empathy, knew straight away what would happen. “This is going to unleash grief like no one has seen anywhere in the world,” he told his press adviser Alastair Campbell.

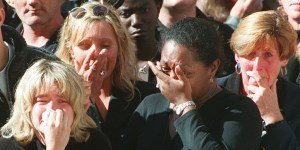

Meanwhile for the public, Blair reached for a quotable headline. “She was the people’s princess,” he told newsmen. The people, desiring to honour their princess, seemed instantly to find the gestures they required. On the Sunday afternoon, as I drove around London with a friend, we watched something extraordinary begin to happen – something that today is commonplace after a tragedy – but then was highly unusual. Crowds were gathering outside the royal palaces. They brought flowers first, and later messages and candles.

These attempts at ritual in a secular nation came from somewhere. Catholic novelist and historian Peter Ackroyd suggested at the time that it was a reblossoming of England’s Catholic sensibility. After all, the biographer of Thomas More pointed out, England was Catholic for 1,500 years before a previous royal had tried to erase the faith from the collective memory. It seemed he had failed.

By midweek, even the aloofness of The Independent was swept aside and our reporters were dispatched to cover this effort at a secular version of Catholic mourning. It was not manufactured; it had begun before the cameras and the reporters arrived. But newspapers’ desire to construct stories did take over later. There was the fuss about flags not flying at half-mast above Buckingham Palace. “Show us you care, ma’am,” one headline demanded of the Queen. Certain papers then tried to whip up a rumpus about a monarch staying away from her subjects, as if remaining in Scotland, caring for grief-stricken grandsons, was an absence of duty.

The Royal Family apparently thought at first that they would have a quiet funeral and bury Diana at Frogmore, the place of rest for that other “troublemaker”, Wallis Simpson. Her family, the Spencers, thought something similar, but wanted it held at the family seat of Althorp. The response from the public and the Blair Government’s view put paid to that. It was to be a state funeral.

In London on the Thursday before the funeral, taking a break from helping to plan our newspaper’s funeral coverage, I walked along the Mall, close by St James’s Palace where Diana’s body lay in the chapel. The rosary given to her by Mother Teresa had been placed in her hands. After the princess’ body was moved to Kensington Palace late on the Friday night before the funeral, Fr Tony Parsons, a Carmelite friar from Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the church by Kensington Palace where Diana used to pray, brought candles to be placed beside the coffin.

But these were not the only touches with a Catholic sensibility; the mood on the streets reminded me of the wake in a Catholic Church on the eve of a funeral, or the night watch on Maundy Thursday: quiet, contemplative, mournful. London has been described as hysterical in those days. It seemed to me quietly sorrowful. Unlike this summer, August 20 years ago was simmering in London: the heat of those August nights could easily have brought out rowdy crowds, but these throngs of people seemed not to be as angry as some reporters were making out.

The day of the funeral brought greater emotion, as the gun carriage carrying the princess’ body left the confines of Kensington Palace to make its way along the mile of streets to Westminster Abbey. Again, it seemed un-English – people calling out “God bless you, Diana”, as they crowded in their thousands to watch the cortège go by while a single bell tolled. Perhaps the sight of her desolate boys joining the cortège from the Mall to walk behind the coffin with their uncle, grandfather and father, put paid to any eggs or insults being thrown at Diana’s former husband.

The Westminster Abbey funeral itself was a combination of Anglicanism and late twentieth-century sentiment, leavened by “Libera Me” from Verdi’s Requiem and traces of Russian orthodoxy from the pen of John Tavener. “May flights of angels sing thee to thy rest,” the choir urged – but there were no prayers said during the service for Diana’s soul. Only Cardinal Basil Hume did so earlier in the week when he sought to console Diana’s Catholic convert mother, Frances Shand Kydd, with a requiem Mass for the princess.

But there were other signs of an emerging, different religiosity at Diana’s funeral. Applause greeted the hearse after the funeral as it began its lengthy journey to the princess’ final resting place on an island at Althorp. Flowers were thrown, scattering in front of her hearse like blossoms honouring the Virgin Mary in a May procession, or the rose petals that fall before the monstrance on a walk for Corpus Christi.

This recovery of long-buried Catholic sensibility paved the way for a new way of grieving in this country. It has been seen since Diana’s funeral when a well-known celebrity, such as Cilla Black or George Michael has died, although in their cases, this secularised Catholic ritual merged with Cilla’s own Catholic funeral and George Michael’s Greek Orthodox one. It was in evidence most recently in Manchester after the terrorist atrocity at the Ariana Grande concert in May this year. There was the same cellophane meadow of floral tributes, candles and images of the dead, although since Diana, the tributes have expanded to include teddy bears. According to Linda Woodhead, professor of the sociology of religion at Lancaster University, who has made a study of these contemporary rituals: “Diana’s death was the turning point. The immediate response was orchestrated by the people, rather than the churches.”

Diana’s death changed the way we talk about death, especially in the immediate aftermath of a tragedy. The language used in comments by relatives of the Manchester victims, after the recent bomb that killed 23 adults and children after a concert, was informally religious. “She is singing with the angels,” said the mother of 15-year-old Olivia Campbell, who was killed in the explosion. The families of victims Chloe Rutherford, 17, and Liam Curry, 19, said in a statement: “On the night our daughter Chloe died and our son Liam died, their wings were ready but our hearts were not.”

“Many of the people who do not have a formal religion do have belief in God, in souls going to heaven, and in angels. They like pilgrimages and candles,” says Woodhead. “This is very different from the Protestant tradition in England. It is like a de-Reformation.”

But these rituals do not just return Britain to its past. They are contemporary too. They owe much not only to English people taking holidays abroad, discovering Mediterranean habits of roadside shrines to the victim of a traffic accident, but to the people who make up the British population today. This population first became very obvious when Diana died; her death brought them on the streets. The people of this princess were from Asia, Africa, Latin America and Europe; they were of no faith, little faith, Muslim, Sikh, but also a substantial number were Catholic too. Modern Britain connected, in that sense, with medieval England, and expressed itself in a mourning ritual that is now the norm.

Catherine Pepinster is a former editor of The Tablet.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0