The Joy of Love: In theory and practice

The Joy of Love: In theory and practice

The Pope’s recent apostolic exhortation emphasises the need for the Church to be sensitive in the way it applies its teaching on marriage and relationships. A moral theologian finds precedents for this approach in diverse areas – from money lending to homosexuality in animals

The Pope’s recent apostolic exhortation emphasises the need for the Church to be sensitive in the way it applies its teaching on marriage and relationships. A moral theologian finds precedents for this approach in diverse areas – from money lending to homosexuality in animals

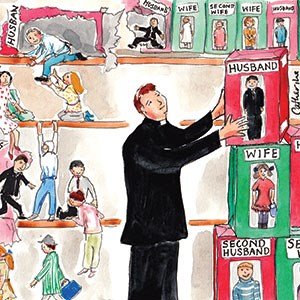

No sooner has Pope Francis’ apostolic exhortation, Amoris Laetitia, appeared than there is an eagerness to claim that it does – or does not – involve a change in church teaching. While more conservative readers do not wish the current teaching to be changed at all, others think it is high time that it was.

I think it would be helpful to make this debate more precise, and to ask whether the document represents a complete change of teaching or, rather more modestly, whether it suggests that existing teaching might be more closely inspected and more considerately invoked in practice without being definitively changed.

A useful parallel is to be found in the practice of civil law: there is a major difference between the way in which our law develops because courts decide how an existing law should be interpreted to deal justly with a particular case, and an alternative process where a law is simply repealed. So, in Britain, what counts as “driving without due care and attention” now might include using a mobile phone, given the effects of such use on a person’s driving, even though those words are not included in the text of the law itself.

It is worth looking at the comparatively simple ways in which some of the Commandments of the Decalogue have been treated in the tradition of the Church. Take, for example, the commandment to keep the Sabbath holy. In Catholic theology that has been interpreted in terms of attendance at Mass on Sundays and perhaps (though with less emphasis) observing Sunday as a day of rest. On the other hand, it is uncontroversially admitted, at least in general terms, that a person is not bound to attend Mass if it is very difficult or impossible for them to do so in cases of illness, or the unavailability of a Mass in a particular locality where an individual had to be.

Similarly, Jesus in the Gospel is presented as saying that keeping the Sabbath holy does not require a person to avoid doing a work of mercy (for instance, healing a sick person, or gathering some berries in order to have something to eat on a journey). Was Jesus “changing the teaching of the Decalogue” or not?

Again, for many years Christians refused to serve in the armed forces, since to do so might involve having to kill someone, contrary to the fifth commandment. Muslims and Christians both, in their different ways, interpreted the lending of money at interest as a kind of theft and decided it must be forbidden. But, in the light of the many possible advantages of being able to borrow money under controlled conditions, both groups have come, by different routes, to similar conclusions, that charging interest on a loan need not, in itself, amount to theft, provided that the interest involved is reasonable and that the lender could, to some extent, be compensated for the risk of losing his money if the debtor was, for some reason, unable to repay.

Muslim law and Christian regulations for the banking industry aim at balancing the interest that is payable against the risks that the lender might be incurring. Are we to say that in such cases they are abandoning God’s law, or are they saying that at least sometimes charging interest over and above the loan does not amount to stealing? (Note, though, that one can still say that some kinds of lending – payday loans to the desperate for instance – are indeed immoral and amount to a kind of organised theft. The devil is in the detail.)

Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas and John Henry Newman are at one in saying that universal principles will often have to be interpreted if we are to make good decisions about particular cases. Most modern legal systems operate under just that assumption. One of Aristotle’s examples involves trying to decide whether to repay a long-standing debt when, on the very day repayment is due, criminals kidnap one’s father and demand a ransom.

Newman’s example is not a moral one, but the principle is the same: Shakespearean critics have over the years formed a very sound judgement about Shakespeare’s language and style, and can edit unclear manuscripts with confidence; but there might, one day, be discovered a manuscript that suggests that they have been mistaken about some texts of which they had previously been reasonably sure.

And Aquinas explicitly says that, unlike the laws of science, moral principles can be very sound when understood in general terms, but the more detailed the circumstances one wishes to include, the less sure we can expect to be that we have got it right.

More than 20 years ago, Cardinal Basil Hume assembled a group of about 20 to 25 people, half of them bishops, half of them teachers of moral theology. He asked us all to offer him some guidance about the admission to the sacraments of the invalidly married.

After a long couple of days’ discussion, all of us, except for one bishop, were of the view that, in considering the case of couples living in a second “marriage”, the key question we should ask is: would we be in favour of insisting that the second family be split up? If, as we thought might usually be the case, breaking up yet another family would be the last thing we would recommend, then there were no grounds for describing their situation as adulterous, and hence for refusing to admit them to the sacraments.

We all remained committed to the sixth commandment, of course, but we took the view that there were many invalid second marriages that could not properly now be described as adulterous. We were not proposing to change the view that adultery is wrong; but we were saying that there can be circumstances for which the description “adultery” is simply unfair.

Rather more speculatively, defenders of natural law as a basis for ethics – of whom I am one – might be interested to know that in most of the more developed animal species there are usually a comparatively small number of individuals who are homosexually oriented. In that case, is it not reasonable to say that homosexual relationships – in those instances – would be natural relative to the individuals involved, and hence, in the case of humans, that homosexual relationships should not be condemned as somehow sinful?

We do not, after all, insist that left-handed persons must write with their right hand, or that people who are in other ways members of a minority group – say those who are deaf from birth, or in some other way disabled, should not be helped to live fulfilled lives even if they cannot function in exactly the same way as the rest of us. In all such matters, a commitment to adapt our practice in accordance with the best information we have about what helps people to live fulfilled lives is what we are called to do. The overall commitment is crucial, and we should be happy to try to work out how best to exercise that commitment in practice.

There is therefore a crucial difference between denying a moral principle, and deciding that it does not apply to some particular type of case. The history of Christian ethics, and indeed the practice of our courts, provides many examples of the importance of this distinction. Amoris Laetitia emphasises the need for sensitivity rather than a rigid interpretation of our teaching.

Gerard J. Hughes SJ is a former master of Campion Hall, Oxford and the author of Fidelity without Fundamentalism.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0