The manuscript that defies science

The Voynich manuscript will be published in facsimile by the Spanish firm Siloé./ Cesar Manso/AFP

For more than ten years, it was an obsession of Juanjo Garcia, 54, and Pablo Molinero, 65, two publishers madly in love with books.

They wished to see with their own eyes, touch with their own hands and, even better, reproduce the medieval Voynich manuscript, conserved for almost 50 years now in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University in the U.S.A.

That’s because the Voynich – from the name of its “rediscoverer” at the beginning of the 20th Century – defies one’s understanding.

It has neither title, author nor date. The writing is unknown, lost, invented or coded. Its drawings are fuzzy. For centuries, its enigma has resisted time and science.

The question as to whether it is an indecipherable major work or a hoax, whether its author was a great mind or a deranged soul has never been settled, even if the most recent scientific studies militate in favor of a real message with a still hidden meaning.

The codex registered as MS 408 is the star of the manuscripts of the Beinecke, the one that too many hands have wanted to handle, including those of eccentrics of all types convinced that they had cracked its secret.

“Yale University also took us for crackpots!” Juanjo Garcia said with a smile. But to protect the manuscript from the risk of degradation or disappearance, Yale ended up consenting to have it reproduced. For this, they selected the masters of the tailormade facsimile, publishers Garcia, and Molinero, creators twenty years ago of the small Siloé publishing house based in Burgos, in northwest Spain.

A stone’s throw from the majestic cathedral, in premises that exude the long history of the medieval castle of Castille, the two publishers receive us in their Museum of Books, which is also home to their publishing house.

“When you look at a manuscript in Latin, you can visualize its context, that of a scribe who devotes himself relentlessly to his writing in his monastery.

"With the Voynich, there is a black hole: who wrote it, where, how, why? That gives you a strange, almost disturbing sensation,” Juanjo Garcia says.

The writing, flowing, regular, gives off a familiar impression, a feeling that understanding it is within your grasp. Yet it resists, closed to all analysis.

Similarly, the plants in the voluminous first part, called the “herbarium”, belong unquestionably to the botanic realm, but “they are Frankensteins with the roots of one plant, the leaves of another and the flower of a third!” exclaims Pablo Molinero.

The work then becomes more esoteric, for 21st-century eyes, plunging into a universe of cosmogonies and a world of miniature women taking baths.

The Voynich thus becomes haunting. “More than one person went mad; Newbold lost his mind over it,” adds Molinero, referring to the American philosopher who died in 1926.

Newbold was convinced that he had broken the code, which he attributed to the learned 13th Century English Franciscan monk, Roger Bacon. Or William Friedman, the head cryptologist of the NSA, the U.S. national security agency, who deciphered the Japanese army codes during World War II, but wracked his brains over the Voynich.

Juanjo Garcia caresses the first reproductions of the vellums, those fine sheets made from the skins of stillborn calves that make up the Voynich.

He does it with his bare hands, of course. “Above all, no gloves,” he says, lashing out at libraries that mandate their use when handling works, no matter how fragile these are.

“You lose the sense of touch and you are less delicate than with clean hands with no sweat or cream,” he adds, as he flaps a few sheets with his fingers, recreating the rustle of someone leafing through a medieval manuscript.

These first replicas are strikingly realistic. The publishers have become experts in aging techniques. “It’s very hard to produce, in the 21st Century, objects that look as if they date back to the 15th Century,” says Juanjo Garcia.

No-one has access to the Siloé’s ultra-confidential aging workshop from where a vellum of another age emerges; not even Virginia Saez, the young historian who guides visitors to the Museum of Books.

“We are counterfeiters,” jealous of their secrets and proud of having deceived sharp eyes, says Juanjo Garcia with a tinge of irony.

When Siloé exposed its first leaves of the Voynich at the Frankfurt Book Fair in October 2016, one of the leaves was submitted for appraisal to reassure an anxious buyer of the good acidity of the vellums – which is a guarantee of the stability of the color over the centuries. “The laboratory refused to analyze it, convinced it was an original,” he explains exultingly.

That’s because, thanks to the collaboration of more than a score of craftsmen specializing in skins, binding, jewelry, etc, everything is reproduced identically, as an aged version of the original.

The variable thickness of the vellum, its irregular slices cut one by one, the wrinkles of the fragile skins and the holes formed by the book-eating worms or by the action of time, the color gradients faithful to the tints of the era, etc.

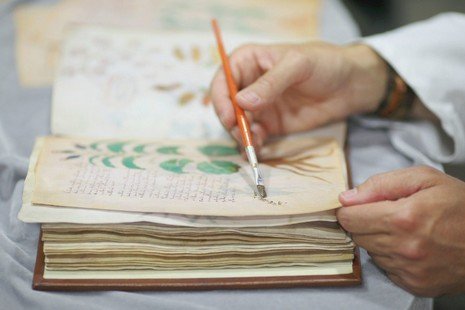

Luis Miguel has the task of making the final aging touches with his small sewing and painting kit, his spools of linen, hemp or raffia and his pots of washed-out colors.

Leaf after leaf, with the patience of a Benedictine monk, the craftsman stitches the small tears, pierces the micro-holes of stitches that have lost their thread.

He dabs at the edges of the holes with the tip of his paint brush to give them a yellowed look and brushes the laced edges to made them red, sending you back to the Middle Ages, when manuscripts were painted to protect them from book-eating insects.

The first complete Voynich is expected to be out by late summer.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0