Thomas Merton reconsidered

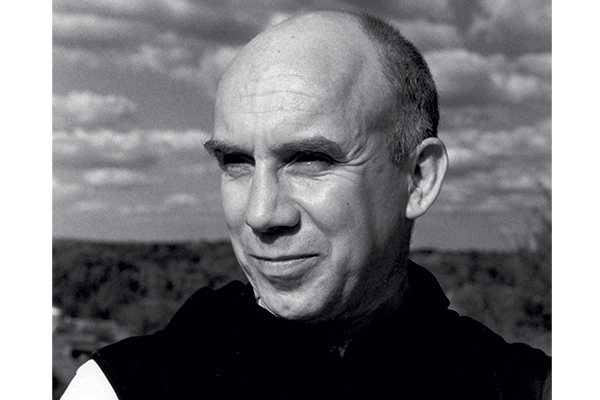

Photo: CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Photo: CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Thomas Merton ‘had trouble balancing things and finding time to pray’

The latest biographer of one of the twentieth century’s greatest spiritual writers has come to terms with the monk’s contradictions and restlessness

How could the monk who was so often upset about his own lack of quiet and solitude also become the most loquacious of communicators? In the last decade of his life, Merton enjoyed correspondence with hundreds of people, including the most renowned literary and religious people of his day – from Boris Pasternak to Joan Baez to Pope John XXIII. When he’d first become a monk, in 1941, Merton thought he was leaving the world behind, before his abbot instructed him to sit at a typewriter in an office, during work hours, and tell his life story. Then, look what happened.

There’s a letter, for instance, that he wrote to one of his publishers in February 1948, several months before The Seven Storey Mountain would be published and make him famous, and in it he begins with a confession: “The devil is trying to mess up all that I do by getting me to do too much and involve me in such a network of projects that I will be neither able to work nor pray.” He goes on to detail his writing projects one by one. Fr Abbot is annoyed that one of his books of poems is out of stock. He needs a Spanish text of St John of the Cross to work more on a project that’s been previously discussed. He needs to write more poems. Meanwhile, another book – which he calls his “book of pensées” – is coming along nicely. (This would become New Seeds of Contemplation.) And his autobiography (Seven Storey) is much too long, and needs trimming. No wonder Merton had trouble balancing things and finding time to pray.

Soon, Merton was beginning to back out of community life, seeking to explore a hermit’s vocation, which was then mostly unknown among the Trappists. For years, he asked his abbot for more access to time alone before being granted what he desired. He knew that in many respects he’d created his own problem; the success of his writings had brought many people to the monastery looking for what this “Thomas Merton” had discovered. For at least a decade before his death in 1968 Merton was instructing young monks as their novice master, guiding them into a monastic life that he was himself, in some ways, seeking to escape.

People often say something like, “Merton was a famous writer who, after a lifetime of giving his words to others, had wearied of fame and needed to place himself before the Unsayable.” I don’t think that’s it. Perhaps Merton was one of those artists who hurt themselves and while hurting themselves create great art. Think of Van Gogh cutting off his ear. Think of Dylan Thomas and Jack Kerouac drinking themselves to death. Think of Kurt Cobain or Sylvia Plath. From his difficult childhood onward, Merton had used his art to seek understanding of himself, knowing full well his flaws, offering those flaws on to the pages of what he created. That didn’t change late in his life. Perhaps, rather, he came to see the flaws themselves as a natural part of a flawed self, seeking salvation. The flaws wouldn’t necessarily go away. He began to see the other side of them.

He saw giving up his public life as a step of finality that he was willing to take. After an afternoon meditating in the woods in the spring before he died, he wrote in his private journal: “I really enjoyed being in the wild, silent spot … And really I am ready to let the writing go to the dogs if necessary, and to prefer this: which is what I really want and what I am here for.” But then a guest from Boston arrives, as planned, that evening, and the monk who a few hours earlier was sure he was made for being “in the wild, silent spot” chats the night away, discussing the things of the world.

We who love Merton and learn from him must accept how he often contradicts himself. This realisation can be frustrating, and can be helpful. He sometimes comes across almost fickle. Truth is, he was constantly “working out” his understanding on paper; he left it for us to see, and we go looking for it. He struggled for years with thoughts of leaving the monastery, or finding a situation that was better. We have to reconcile this with what he writes near the end of chapter 35 of that classic, New Seeds of Contemplation: “Fickleness and indecision are signs of self-love. If you can never make up your mind what God wills for you, but are always veering from one opinion to another, from one practice to another, from one method to another, it may be an indication that you are trying to get around God’s will and do your own with a quiet conscience. As soon as God gets you in one monastery you want to be in another.” At times, Merton is writing to himself.

An analogy may be helpful: my wife and I like to take long bike rides. The purpose of a good bike ride for her is mostly about the exercise. She’s an athlete and I’m not. The exercise is, for me, only one part. When we plan a ride, I prefer that we are headed somewhere: a park, a tavern, downtown, a friend’s house. Simply hauling down a bike path, turning around and cycling back, doesn’t really interest me. For me, the journey (or the ride) is not enough in itself. I want to feel as if I’m going somewhere. I think that Merton wished he could feel about the spiritual life the way my wife feels about bike rides – with a sort of purity of intention – but he couldn’t really do that. For whatever reason, he found that that wasn’t in him. In the end, he wanted to be going somewhere.

Would that all of us were as self-aware as Merton was, and as willing to honestly reconsider who we are as we tackle the journey of lifelong conversion.

Jon M. Sweeney is a writer and publisher, whose many books includes history, spirituality, poetry/mysticism, memoir, and young reader fiction; Thomas Merton: An Introduction to His Life, Teachings, and Practices (inset) was recently published by St Martin’s Press at £11.99 (Tablet price £10.79).

Votes : 0

Votes : 0