Understanding the Ascension

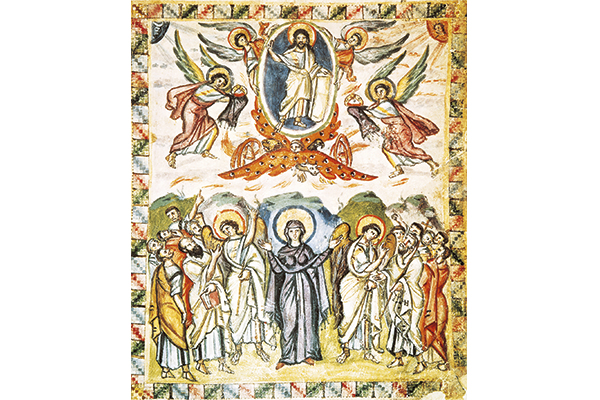

Christ’s Ascension, miniature from the Rabbula Gospels, Syria, sixth century. Photo: Bridgeman

The Ascension, which the Church celebrates this Thursday, is often misunderstood as the moment when 40 days after Easter Christ suddenly vanished from the earth. As a Cistercian abbot explains, the true story of the Ascension is very much more attractive and mysterious

This summer, a half-century will have passed since man first landed on the moon. In mid afternoon on 16 July 1969, a spacecraft named Apollo 11 was launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, entering earth’s orbit after 12 minutes. Three days later Apollo 11 passed behind the moon and entered the lunar orbit.

On 21 July, at around the time when Cistercians rise for Vigils, the astronaut, Neil Armstrong, opened the spacecraft’s door and set foot, the first man in history to do so, on the surface of the moon. In a thoughtful phrase, he remarked that his small step was “a giant leap for humankind’’.

The mission, which has left its mark on our consciousness, was a scientific triumph. But for our theological imagination, it was a disaster. It especially confused our notion of the Lord’s Ascension. The readings set for the liturgical solemnity culminate in these words: “Now, as he blessed them he withdrew from them and was carried up to heaven.” For us, who live in the wake of the 1969 lunar mission, it is almost impossible to hear them without seeing before our mind’s eye the Apollo rocket fired off from Camp Kennedy.

If we stay within the logic of the image, we are faced with massive conundrums. If Christ took off from earth in that sort of way, where did he go? Is heaven a place out there beyond the galaxies, a place we might reach by our own endeavours one day, given adequate technical know-how? Or was Jesus transported straight to the Father’s bosom? If so, divine realities being immaterial, was he transformed from a person with a body to a purely spiritual being in mid air?

You may sneer at these rhetorical questions. You may think I am trying to be funny. I am not. Too often have I seen and heard the Ascension represented on the basis of such assumptions. The feast calls forth quite absurd associations. I dare say that is why so many do not know what to make of the Ascension. It seems too much like a cartoon solemnity, a feast one cannot take entirely seriously, one of those occasions when faith requires more than is reasonable.

As it happens, Scripture provides two accounts of the Ascension by the same author. St Luke informs us that he was not an eyewitness to the life of Christ, but that he had carefully interviewed eyewitnesses, and he collates their testimonies in a coherent narrative that grows in subtlety as, little by little, he comes to understand his sources better. The account I have cited (“as he blessed them he was carried up to heaven”) comes from his gospel (Luke 24:51). It is instructive to compare it with the later Lucan account in that gospel’s sequel, the Acts of the Apostles. The passage is read to us at Mass on Ascension Thursday. It recounts how, with the Apostles looking on, Jesus “was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight” (Acts 1:9). No longer is it suggested that the Lord shot into the firmament. No; “a cloud took him”.

In the Bible, a cloud is not just something to do with the weather. When Israel walked out of Egypt, “the Lord went before them by day in a pillar of cloud” (Exodus 13:21). The cloud was a sign that God was in their midst. When Moses scaled Sinai to stand before God, the Lord descended in a cloud. It was likewise in a cloud that, later, he filled the tent of meeting with his presence. By the book of Numbers, the cloud has become an established symbol of God’s nearness. This connection is further developed in the historical books. What happens when the temple in Jerusalem is finished, the building work all done? What makes a mere monument into a sanctuary? At the moment of dedication, “a cloud filled the house of the Lord, so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud; for the glory of the Lord filled the house of God” (2 Chronicles 5:13-14). The cloud is glory. The glory is presence. It tells us that the Lord, the Father of all, is there.

Read in this light, the Ascension story is not only less perplexing, it is very much more attractive and mysterious. The conclusion of Christ’s earthly ministry turns out to be continuous with a long history of divine self-revelation. It is a moment of epiphany. In terms of Christ’s career, the Ascension cloud recalls the cloud that covered the Mount of Transfiguration, from which the Father’s voice announced, “This is my Son, my Beloved” (Luke 9:35). It points forward, too, to the Lord’s definitive coming at the end of history. Luke gives us the very words of Jesus. Speaking of trials to come, he assures his disciples that they will see “the Son of Man coming in a cloud with power and great glory” (Luke 21:27). On that day, the cloud will announce the completion of time.

The message of the Ascension is not that Christ vanishes beyond earth’s orbit, but that he enters the Father’s glory, which is set to fill the earth (Numbers 14:21) by way of preparation for the glory of eternity. This prospective aspect of the Ascension made it central to early Christian thought and practice, splendidly evidenced in the illustration shown here from the Rabbula Evangeliary, a sixth-century Syriac manuscript. The cloud is transmuted into a nimbus of gorgeous imperial purple, a symbol of the majesty arraying Christ as he rides in the chariot Ezekiel saw, drawn by the four living creatures – ox, eagle, lion, man – that, by Rabbula’s day, had lent their features to the evangelists. Worshipping angels acknowledge Christ’s kingship by offering him crowns, while the Spirit’s attributes, wind and fire, rush through the firmament in almost perceptible movement, a whoosh carrying across 15 centuries. There is a wonderful vitality to this scene, with everyone’s attention focused on the same object of longing and love. The Virgin is no exception, though so interior is she that she ponders everything “in her heart” (Luke 2:51). Christ, erect, presides over the cosmos, his right hand raised in blessing, his left propping up the unhinged door of hell. With time, this image would metamorphose into the seated Pantocrator we know from the apses of Byzantine basilicas, a motif representing the Ascension, as it were, by implication.

To prepare for the Nativity of Christ, the Church invokes him with the words, “O Oriens”. The early Christians expected his second coming, too, from the East. That was the reason for their orientation in prayer. They turned east to enact their certainty, derived from the Ascension, that Christ will come again, that history has a goal, that the universe awaits fulfilment. Look closely at Rabbula’s illumination and you will see that the sun and moon are not impersonal fixtures but endowed with faces, parts of an intentional creation directed towards its maker.

It is impressive to note that the mere mention of “orientation” nowadays, instead of enflaming contemplative yearning, is likely to provoke the crossfire of liturgical guerrilleros; that we, unlike Rabbula’s Christians, readily point fingers at each other, but rarely heavenward; that the cloud in which Christ, to this day, reveals his presence is apt to pass us by unnoticed, blinded as we are by pollutant polemics that fill the Church like smog; that we view the world around us (including, now, the moon) as mere matter for exploitation, not as a significant whole that indicates God’s promise.

Are we alive with the eschatological tension that set our Christian ancestors’ hearts on fire, inspiring them to perceive Christ’s Ascension, not as a barrier, but as an opened door by which eternity and time meet in a burning, infinitely desirable embrace? Should the answer be no, it is small wonder that we are prone to turn in on ourselves and fall out with one another. In the Collect for the Ascension we pray that as Christ, by his promise, “remains with us on earth, we might be made worthy to live with him in heaven”. The Ascension represents a call to conversion, to turn round together – an orienting call.

Dom Erik Varden is abbot of Mount Saint Bernard Abbey in Leicestershire. He is the author of The Shattering of Loneliness, published by Bloomsbury at £10.99 (Tablet price, £9.89).

Votes : 0

Votes : 0