‘With a sorrowful heart …’ - the scandal of abusive priests

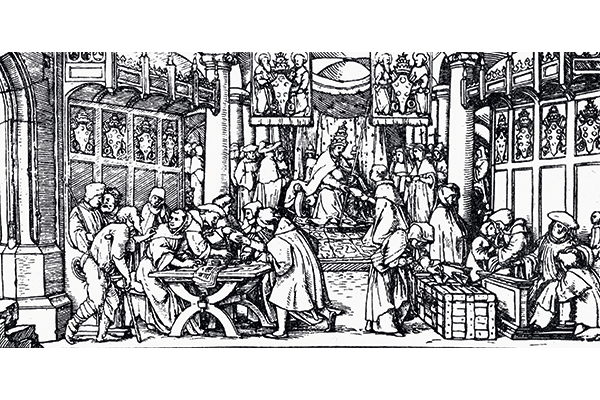

Today, the abuse scandal is playing a role similar to that played in the High Middle Ages by the indulgence scandals that accelerated the Reformation’ - Alamy/Interfoto (woodcut attributed to Hans Holbein the Elder)

The scandal of abusive priests has devastated thousands of lives and exposed a crisis of faith. Addressing an international conference on the issue in Warsaw last month, one of Europe’s leading Catholic intellectuals argued that only profound reform can save the institutional Church

In a spirit of humility and with a sorrowful heart – in spiritu humilitatis et in animo contrito – I want to touch on one of the most painful wounds of the Church. Even the mystical body of the Risen Christ bears wounds, and if we ignored these wounds, if we did not want to touch them, we would not have the right to say with the Apostle Thomas, “My Lord and my God!”. According to an old legend, the devil himself appeared to St Martin in the form of Christ. But Martin asked him: where are your wounds? A Christ without wounds, a Church without wounds, a faith without wounds, is just a diabolical illusion. With courage in the healing and liberating power of the truth, we want to touch the wounds inflicted by Catholic clergy and church officials on the defenceless, especially on children and teenagers, and thus on the credibility of the Church in today’s world.

To understand this crisis and to accept it as kairos, as a challenge and an opportunity to mature our Church and our faith, we need to see and address the phenomenon of clerical abuse in a broader context. The survivors and victims of abuse must be at the centre of our concern. We must give them all the legal, psychological and spiritual support they need. The guilty must be punished, and helped on the path of repentance and healing. Practical measures must be taken to minimise the risk of children and vulnerable adults being abused in the future. But all these important steps are only a small part of what we are obliged to do.

Both Benedict XVI and Pope Francis have shown the right way: we need to ask what has happened to our Church, what has happened to our faith, that made it possible for something like this to happen. In many places in the world, the Church has become a “political apparatus” rather than a community of faith, as Benedict has observed. The Church must rid itself of the disease of clericalism, because cases of abuse are, above all, cases of abuse of power and authority in the Church, as Pope Francis repeats. It is not just a matter of individuals; it is a dangerous disease of the whole system. To minimise the problem of abuse, to claim that the problem is even greater outside the Church, or to claim that the problem only concerns some local Churches, shows spiritual blindness, hypocrisy and pride.

This international conference on the sex abuse crisis is being held in Warsaw because it is in the post-communist world that we often see these attitudes. We must radically reject the diabolical temptation to claim that the problems of sexual, psychological and spiritual abuse are diseases of the “corrupt West”. Overlooking the beam in one’s own eye makes it impossible to see serious phenomena realistically and to address them effectively.

There are a number of reasons for the tendency in post-communist countries to deny the problem of clerical abuse. It is true that in many countries under communist rule, priests had fewer opportunities to abuse minors because, unlike in the free world, there were almost no church institutions dedicated to the care of children and youth. And totalitarian regimes, both Nazi and communist, often tried to discredit the Church and particular priests by falsely accusing them of sexual abuse. (Perhaps this is why Pope John Paul II for a long time did not believe many of the accusations against priests.) Today, with access to the archives of the secret police, we can see that the communist regimes were well aware of real cases of abuse and other dark aspects of the lives of priests such as alcoholism or corruption; they often blackmailed these priests and some became informants.

When there was state persecution of the Church, internal cohesion and solidarity was fostered. But the flip side was an unwillingness to see the dark shadows within its own ranks. After the fall of communism, conservative Catholics from the West came to our countries, wanting to portray the Church as a Sleeping Beauty who had happily slept through the time of the Second Vatican Council; like a prince from a fairy tale, they would awaken her with a kiss to her premodern beauty. The Sleeping Beauty must of course have no ugly features – hence no abuse scandals.

This false image is gratefully endorsed and internalised by some Catholics in post-communist Europe: we are the Church of the Martyrs, cleansed by our persecution, who will now teach moral lessons to the “corrupt West”, including Catholics in our sister Churches in western Europe and North America. Ex Oriente lux, ex Occidente luxus (“From the East comes light, from the West comes luxury”)! This ideology needs the picture of the “corrupt West” as a world of consumerism, materialism and liberalism, in contrast to the “Holy East”, the heroic persecuted Church. The reality of a Church that itself causes suffering does not fit the image of a suffering Church of martyrs. But the truth is rarely black and white.

This seductive self-illusion of a purer Church of the East took hold in post-communist Europe for many reasons. After the fall of communism, some Christians could not live without the enemy. The “corrupt liberal West” became the ideal replacement for the old enemy. Catholics, once persecuted by the communists, now began to use the anti-western rhetoric left in their subconscious by the brainwashing of communist propaganda. The messianism of some nations and local Churches, a legacy of romanticism (not only in Poland and Russia), also played a role. The concept of the “chosen ones” (the images of the suffering Messiah and of a suffering people) helped the Churches survive in times of persecution; but, after the fall of communism, when the sad consequences of persecution and isolation became apparent, these self-images became compensation for the inferiority complex felt towards the West.

The assumption that the Church had slept through the Second Vatican Council and its reforms during communism was only partially true. I remember with gratitude my teachers in the faith, who had spent long years in Nazi and then communist prisons and concentration camps or in forced labour in uranium mines. There they experienced “concrete ecumenism” – nearness and fraternity not only with Christians of other Churches, but also with secular humanists and even with nonconformist Marxists. Some of them, in the spirit of the prophets, embraced the years of persecution as a divine lesson, a purification of the Church from its earlier triumphalism. In prison, they dreamed of a future form of the Church – an ecumenical, open, poor and serving Church. When they were released from prison in the late 1960s, they embraced the reforms of the Council with enthusiasm and understanding as a God-given challenge. They introduced me and many others to the spirit of the Second Vatican Council. I feel personally obliged to be faithful to their testimony.

The vast majority of priests and bishops, however, did not have access to contemporary theological literature and did not have those experiences. Not knowing the intellectual context, they could not fully understand the message and meaning of the council. Reforms often remained superficial and purely formal – the altar was turned, the national language was introduced into the liturgy. But the mentality did not change. The council’s efforts to move “from Catholicism to Catholicity”, to end the futile culture war with the modern world, and, above all, to abandon a clerical understanding of the Church, remained misunderstood and unfulfilled in much of the Church under communist rule. It suited communist regimes to preserve the clerical model of the Church: in many countries, priests were employees of the communist state and could be manipulated by the state more easily than the laity.

The situation in each country was and is different. Hard secularisation during communism and “soft secularisation” in the post- communist era took place and is taking place with varying intensity. In some countries, paradoxically, communist persecution brought about a revival of religiosity, albeit short-lived. In Bohemia, the western part of the Czech Republic where I come from, cultural secularisation had been going on since the late nineteenth century as a result of industrialisation, urbanisation and a good education system; during communism, the Stalinists chose Bohemia – probably because of its dramatic religious history and tradition of anticlericalism – as a suitable terrain for an attempt to create a totally atheist society. But after a brief religious revival before and after the fall of communism, when the Church enjoyed great sympathy in society, the Church proved unable to respond adequately to the challenges of the new era. Another wave of “soft secularisation” has arrived.

In neighbouring Poland, the situation was quite different. Until recently, the folk religiosity – the Volkskirche – had its socio-cultural biosphere in a predominantly agrarian society. Catholicism was understood – unlike in Bohemia – as an integral part of national identity. During John Paul II’s first visit to his homeland in 1979 after his election as Pope, it became clear that the Church had a far greater moral, psychological and political influence in Poland than the communist government. The critical moment came only at the moment of John Paul II’s death – the Church now faced the task of rediscovering Christ and the Gospel behind the icon of the holy Polish Pope. The unfortunate alliance of some of the bishops with the current populist and nationalist government has damaged the Church in Poland far more than half a century of communist persecution. The current wave of revelations of a pandemic of abuse in distant and recent history has caused an earthquake in the Polish Church. Sexual abuse was only one aspect of the problem. Unless the Polish Church now manages to understand the current crisis as a kairos and a call for deep reform, unless the Church reveals to Polish society – and especially to the young generation – a different face of Christianity, the process of secularisation in Poland will be even more radical than it has been in Spain and Ireland.

The sexual abuse crisis is not marginal. Today, the abuse scandal is playing a role similar to that played in the High Middle Ages by the indulgence scandals that accelerated the Reformation. What at first seemed to be a marginal phenomenon, is today – as then – revealing a much deeper problem. The whole system is diseased: the relations between the Church and political power and the relations between clergy and laity, among many others.

The situation of the Catholic Church today strongly resembles the situation just before the Reformation. The Church needs a profound reform. If we limit this to institutional changes, the reform will remain superficial and could lead to schism. We need to take inspiration from the Catholic Reformation of the sixteenth century – its essence was a deepening of spirituality throughout the Church (think of the role played by mystics such as Teresa of Avila, John of the Cross and Ignatius of Loyola), but this period also saw the emergence of a more pastoral style of episcopal and priestly ministry (think of Charles Borromeo and many others). It is necessary not just to change structures but to change the mentality, to change the culture of relationships within the Church.

Many reforms in the Church in the past have only come after tragic delays. In the nineteenth century, the Church lost the working class. In the early twentieth century, it committed intellectual self-castration in a struggle against so-called “Modernism” that led to the loss of a large part of the intelligentsia and many prophetic personalities. In the 1960s, it lost a large part of the younger generation, and now – in the era of a new self-understanding of the dignity of women – it is losing women. The Second Vatican Council’s efforts to come to terms with the modern world also came too late. While modernity peaked in the 1960s, it ended soon after.

The council did not prepare the Churches for the postmodern age. Today the whole sociocultural context has changed. The Churches have lost their monopoly on religion. Secularisation has not destroyed religion, but transformed it. The main competitor to the Church today is not secular humanism, but new forms of religion and spirituality that have emancipated themselves from the Church. The Church is finding it difficult to find its place in a radically pluralistic world. And the Churches marked by their communist past are finding it particularly difficult to orientate themselves in this world.

The Church reacted to the sexual revolution of the 1960s with moral panic. The emphasis on sexual morality became the dominant theme of preaching, and a gap opened up between church doctrine and the lives of many Catholics, including priests. No topic was discussed by the Church as often as sex. The Sixth Commandment often came first in sermons. Pope Francis has had the courage to call this by its proper name: “neurotic obsession”. And as the abuse scandal has unfolded, the reaction inside and outside the Church to these moral lectures has been, naturally enough, a furious, outraged “Look at yourselves!” The Church has been late – perhaps too late – to begin to address this hypocrisy and scandal within its ranks, and then often only in response to the exposure of abuse and its cover-up by the secular media.

I am concerned that many seminaries (especially in post- communist countries) do not provide candidates for the priesthood with sufficient spiritual and psychological preparation for a life of celibacy. This must include an honest discussion of homosexuality, including the homosexual orientation of many priests. Some priests cope with their sexuality through a mechanism of projection: the most belligerent voices against homosexuality in the priesthood are often priests of homosexual orientation. The Church has paid the price for having resisted for too long the insights of cosmology, evolutionary theory and literary and historical criticism in biblical exegesis; it should not repeat these mistakes by ignoring the insights of neurophysiology in its approach to homosexuality and of cultural anthropology in its understanding of the development of family life.

“This time is not just an epoch of change, but a change of epoch,” Pope Francis has said. The roles of religion and Churches in societies and cultures are changing radically. Secularisation has not caused the end but the transformation of religion. The culminating process of globalisation is encountering resistance: populism, nationalism and fundamentalism are on the rise. Our world is increasingly interconnected and at the same time newly divided. The global Christian community is increasingly divided too – but today the greatest divisions are not between Churches, but within them. I saw the closed and empty churches during the coronavirus pandemic as a prophetic warning sign: this may soon be the state of the Church if it does not undergo deep reform.

The abuse crisis is only one aspect of the crisis of the clergy as an institution, the crisis of the Church and the crisis of faith. This crisis can only be overcome by a new understanding of the role of the Church in contemporary society – the Church as a “pilgrim people of God” (communio viatorum), the Church as a “school of Christian wisdom”, the Church as a “field hospital” and the Church as a place of encounter, sharing and reconciliation. We must face this crisis without fear or panic, with confidence in the Lord of history. The solution presupposes a calm and thorough spiritual analysis, a spiritual discernment. According to an old Czech legend, the builder of a Gothic church in Prague set fire to the wooden framework when the building was finished. When the fire ignited and the scaffolding fell to the ground in flames with a roar, the builder succumbed to panic and committed suicide, believing that his building had collapsed. It occurs to me that many Christians who are panicking in this time of change are falling into a similar error. What is collapsing may be only a wooden scaffolding; when it burns down, the church building will certainly be scorched by fire, but the essentials that have long been covered up will be revealed.

In my 43 years of priestly ministry, I have heard tens of thousands of confessions. For many years, in addition to the Sacrament of Penance, I have offered “spiritual counselling”, which is longer and deeper than what the ordinary form of the sacrament allows. These conversations are often attended also by unbaptised “spiritual seekers”. I have expanded my team of collaborators for this ministry to include laypeople trained in theology and psychotherapy. I firmly believe that “spiritual accompaniment” will be the most important pastoral task of the Church in the coming age.

It is also the ministry in which I myself have learned the most, in which there has been a certain transformation of my theology and spirituality, of my understanding of faith and of the Church. When my bishop, the Archbishop of Prague, resolutely refused to speak to victims of sexual abuse by priests (including members of the monastery of which he was superior at the time) and referred them to the police, I spent long late-night conversations with many of them. Afterwards, I often found I was unable to sleep until morning. I did not learn much more than what had already been reported. But I looked these men and women in the eye and I held their hand when they cried. It was very different from reading their statements in court documents. I have worked for years as a psychotherapist and I know about the proximity and the interplay of mental and spiritual pain, but this was something other than mere psychotherapy; I felt the presence of Christ there with all my heart, on both sides: in the “little ones, the sick, the imprisoned and the persecuted” and also in the ministry of listening, consolation and reconciliation that I was allowed to give them.

I often return to a short story that is a kind of mini-gospel in the middle of Matthew’s gospel, the story of a woman who suffered from a haemorrhage for 12 years, tried many doctors, spent all her fortune on treatment, but nothing helped. According to the religious officials of the time, a bleeding woman is ritually unclean, not allowed to participate in a service, and no one is allowed to touch her. The woman’s compulsive desire for human intimacy, for human touch, led her to the act of breaking the commanded isolation: she touched Jesus. She touched him anonymously, from behind, trying to remain hidden in the crowd. But Jesus did not want her to be healed in this way. He sought her face. The woman came forward, and after years of hiding and isolation, she finished what her body had been saying – in the language of blood and pain – by prostrating herself before him and “telling the whole truth” in front of everyone. And in that moment of truth, she was liberated from her illness.

I dream of a Church that would create such a safe space – a space of truth – that heals and liberates. It is my sincere hope that this conference will contribute to the fulfilment of that dream.

• Tomas Halik is professor of sociology of religion at Charles University, Prague, the city where he was born in 1948. He is president of the Czech Christian Academy and pastor of the Academic Parish of St Salvator. He holds honorary doctorates in theology from the universities of Erfurt and Oxford. His books, which are best-sellers in his own country, have been translated into 19 languages and have received several literary prizes. Under the communist regime, he was secretly ordained as a priest in Erfurt and was active in in the underground Church while working as a psychotherapist. He was one of the closest collaborators of Cardinal Frantisek Tomasek. After the fall of the communist regime in 1989, he was secretary general of the Czech bishops’ conference and an adviser to Vaclav Havel. Pope John Paul II appointed him adviser to the Pontifical Council for Dialogue with Non-Believers in 1990; Benedict XVI named him honorary pontifical prelate in 2008. He has received numerous international awards and prizes for his contribution to the Church in times of persecution, and for dialogue between religions and cultures. He was awarded the Templeton Prize in 2014.

Votes : 0

Votes : 0